Ferrill Roll, CIO: We’ve convened this discussion because after coping with four years of US-originated turbulence in Chinese equities—from tariffs and trade wars, to congressional action against Chinese companies listing in the US that hadn’t gone through the usual US auditing requirements, to executive orders prohibiting Americans from owning companies controlled by the Chinese military—we are now faced with turbulence in Chinese equities that has originated from Chinese regulatory actions. In that new, different environment, we thought it would be useful to discuss how we cope with this, what’s actually going on, and what our thinking is for the future.

First, I’d like to comment about our risk guidelines at Harding Loevner. We insist on diversification in all our strategies. And insofar as that pertains to Chinese equities, you will recall that it was just a year ago that we were in lively discussions about the limit that we had placed on Chinese equities—in our Emerging Market Equity strategy in particular but, in fact, in all of our strategies. We had set our limit—when times were calm, and we were being thoughtful about the future—at a maximum weight of 35% in China for a diversified emerging market portfolio.

When China managed to get the coronavirus under control faster than the rest of the world, Chinese shares surged relative to everywhere else. Our emerging market PMs were chafing under the inability to own as much as the index, let alone go overweight, in China. Clients were asking us questions about how we could be so ultra-conservative as to constrain our PMs from doing whatever they needed to achieve returns. And, frankly, we had rather tense discussions among our partners as some clients thought about leaving Harding Loevner as a manager because of our intransigence over these risk controls.

We think of our risk controls as constraints against our future selves—in the way that Ulysses tied himself to the mast before he passed by the sirens that would otherwise have lured him to destruction. We thought when we were setting our limits on China that they were sensible. A year on, we are now flooded with client calls about, “How much risk do you have in China? What are your exposures to the companies being buffeted by these regulatory shifts?” And we feel vindicated that we stuck to our pre-commitments. This is a well-established area of behavioral finance, that pre-commitments are the hardest things to keep when they are the most important things to keep. I think this is a lesson that we will take with us through the years going forward.

That said, Harding Loevner has a very clear long-term outlook that China is going to be a fruitful place to invest our clients’ money and to hopefully add value using our process of fundamental analysis and valuation. We launched our first single-country strategy, the Chinese Equity strategy, late last year. So, we’re optimistic that we will find lots of ways to add value in China.

Pradipta, you’re the Lead PM for the Chinese Equity strategy. Your entire portfolio is subject to these recent regulatory shifts. Why don’t you give us a quick summary of what’s happened recently and how it’s affected you?

Pradipta Chakrabortty, Lead PM Chinese Equity: So, there have been a slew of regulatory actions across different sectors and industries. I classify them under four buckets. First were the antitrust regulations that manifested through fines on Alibaba and moved on to fines on other companies in the internet space such as Tencent and Meituan. That has subsequently moved on to breaking down several barriers and walls that these gigantic platform companies had created around themselves.

The second bucket relates to the stability of the financial services sector and was manifested through regulations that resulted in the cancellation of the Ant Financial IPO. The third area, data security regulations, is much more recent. Immediately after the IPO of the ride-hailing service Didi Chuxing, you saw cybersecurity concerns emerging, leading to restrictions of Didi’s ability to onboard new users. And the fourth bucket, social issues-related regulations, is pretty broad across different sectors. One of those sectors affected was after-school tutoring, where you had severe restrictions, converting that industry into not-for-profit. This week, we saw news about concerns about how online gaming affects children. So that sector has been under a little bit of pressure. There’s also been noise around the gig economy and fair compensation for workers there.

So, it’s a whole gamut. The net result is that investors have been spooked. The MSCI China All Shares Index is down close to 8% in the first seven months of the year, underperforming the MSCI ACWI Index, which is up 13%.

FR: Jingyi, can you talk to us about the high-level goals the Chinese government is pursuing with all these changes?

Jingyi Li, Co-Lead PM Global Equity: The Chinese government’s long-term goal is to continue to develop the economy. It has done a good job leading China from a low-income country decades ago to where it is a mid-income country today. And it has showed the ambition to continue to grow the economy in the next decade or 15 years to become an entry-level developed country. That means the economy needs to grow around the mid-single digits for the coming one or two decades at least.

To continue to drive the economy to reach the next level, you need a lot of structural reforms, reforms that we have seen, but also at the same time, you need to address a lot of social issues. Some are social issues caused by new economies and new technologies. Some are common issues everywhere in the world, like inequality, like the competitiveness of the labor force. Without addressing these kinds of long-term profound social issues, the Chinese government—who rely on long-term growth as one of the key legitimacies of their government—is concerned that they may not be able to continue on this trajectory, just like many Latin American countries stuck in the so-called mid-income trap.

FR: Craig, would you agree that’s the main goal, or do you think there are some more jaundiced, pernicious goals that the government is pursuing?

Craig Shaw, Co-Lead PM Emerging Market Equity: China is run by the Communist party. It is not a democracy. You could call it a dictatorship, and the way they stay in power is by keeping people happy. There’s an old Chinese saying that the emperor will reign in heaven until the people throw him out. And that’s proven to be true over much of China’s history. They are doing their best to stay in power and keep their people happy, which is something we always have to be cognizant of.

There’s an old Chinese saying that the emperor will reign in heaven until the people throw him out. And that’s proven to be true over much of China’s history.

FR: So, you don’t think they’re going after companies that have skirted the domestic listings rules by raising money outside? You don’t think they’re targeting prominent individuals who made a lot of money and turned that into a personal soapbox for their own use?

CS: Well, those are issues. We’ve seen this over the decades in emerging markets. Remember how in Russia Mikhail Khodorkovsky at Yukos got involved in politics and lost everything and was in prison for quite a while. To a certain extent, if someone becomes influential and wealthy and powerful, they are perceived, whether they really are or not, as a threat to the government’s control over the population. It’s a risk. We certainly saw that with Jack Ma at Alibaba a little while ago, when he made some comments about the future of finance in China. And the powers that be didn’t seem to like it.

FR: Andrew, before you became Co-Lead PM of the International Equity strategy, you were the manager of research. In fact, you started at Harding Loevner as an emerging market analyst. So, you’re deeply familiar with how we think about regulation in the structure of our research process. Can you lay out for us how we assess regulation?

Andrew West, Co-Lead PM International Equity: Sure. We have three key features of our process that leads to us being aware of regulatory risk and reacting to it, and hopefully anticipating it. One is our constant analysis of Porter’s “Five Forces” that dictate industry structure. For each of the five—whether it’s bargaining power of buyers or suppliers, rivalry, threat of new entrants—we ask our analysts to both understand the existing regulatory issues that may influence those forces and to keep an eye out for incoming potential changes that could influence them. It’s all part of helping us understand the trajectory of profitability in the future, of growth opportunities, and helping us reflect that in our forecasts. The second key feature is our ongoing monitoring of environmental, social, and governance (i.e., ESG) risks. And third is our requirement of higher returns from riskier countries, where we tilt our valuations of stocks based on the riskiness of the countries in which they’re operating.

FR: I’m interested in the ESG analysis. At Harding Loevner, ESG analysis is really a risk analysis rather than a pursuit of return of goodness, if you will. We’ve had a lot of client inquiry over the last two years about the E part of ESG, and almost no inquiry about the S—the social part. Do you think that we have underemphasized the regulatory risks that have emanated from these social risks in ESG in the case of China?

AW: It is a topic that we have actively debated. And social risk is a risk. A lot of the concern has been around looking from the outside in, with international companies and other countries threatening China in some way over their internal political activities. But there are also internal social pressures inspiring new regulations. And that ties into what Jingyi spoke about before, when you asked him about the goals of the Communist party.

Have we under-recognized it? I would say the market has revealed an under-recognition of regulatory risk. Just a year ago, there seemed to be no fear built into prices. And now there’s a lot of fear built into prices. Awareness of that comes and goes. I think the actions in some industries were harsher than just about anybody would have forecast. Even if we’d been aware of the pressures for change, we may not have anticipated such sudden and violent regulatory reaction to those pressures.

I would say the market has revealed an under-recognition of regulatory risk. Just a year ago, there seemed to be no fear built into prices. And now there’s a lot of fear built into prices.

FR: Pradipta, in addition to your new role as a Lead PM of the Chinese Equity strategy, you have long been Co-Lead PM on the Frontier Emerging Markets Equity strategy. You’ve invested in a bunch of countries that have a lot of risk. How do you assess risk in China versus the regulatory risk in China versus the regulatory risk in, say, Turkey, which has an authoritarian president?

PC: I mean, Turkey is obviously a different case altogether. You can’t really put it in any bucket. But in several other frontier countries—Kenya, Nigeria, the Philippines—they all have a significant amount of regulatory risk, and we’ve seen regulatory actions in those markets. The difference is in terms of the communication and the transparency of the debates that go on in the public domain. In most of these other countries, you would see lawmakers and regulators going through a lot of public debate where you’re privy to their thoughts and their potential future actions, much more than you would in China.

But to be fair to the Chinese regulators, there have been hints about each of these regulations that have been enacted this year. The problem is that those clues have been rather cryptic and the end result quite shocking. For example, the after-school tutoring sector having been converted into a not-for-profit—there was really no clue about that coming. So, I would say communication is where there is definitely more work to be done by the Chinese regulators. If they do communicate their intentions or their thinking more clearly, there would be less disruption in the markets.

FR: Craig, you mentioned Russia and the case of Yukos and the expropriation of assets in that case. That was at least as shocking as the vaporization of billions of dollars of market value of these Chinese education companies. How do you think about risk in China versus regulatory risk or expropriation risk in Russia or any other of the emerging market countries that you’ve invested in over the last 20 years?

CS: China’s a little different. You can argue how effective democracy is in some of the emerging markets, but at least they are democracies, to some extent. Whereas China is not. And so, the government has total control over everything. They debate within themselves, but as far as dealing with representatives of the populace, it’s a little different. They have a lot more control and a lot of these moves that we’ve seen are all about enhancing that control.

If you look at Russia, it’s changed quite a bit over the years. There was a time that share prices would fall 20% if Putin was annoyed with something. Certainly, Putin has a great amount of control over what happens. But he has not been overly aggressive in terms of doing anything to industries. I mean, if you go back to the Yukos case, there was an arrangement made a long time ago when Putin first came to power, that he would let the oligarchs keep whatever they managed to gather during the chaos of the fall of the Soviet Union as long as they stayed out of politics. And to a large extent, he’s kept that promise. But he certainly can scare people.

FR: Presumably, you’ve come to rely on that, because you’ve been overweight Russia in your emerging market portfolio for five years.

CS: Yes. It’s not the easiest place to be, but we do what our process and philosophy guides us to, and have found some good quality-growth companies at reasonable prices.

FR: It’s one thing for emerging market or frontier emerging investors to parse these risks because they’re all risky neighborhoods, and each one is risky in its own way. But Jingyi, you’re now a global portfolio manager, having concentrated on China for a long time as analyst. How do you compare the regulatory risk in China versus the regulatory risk in the US?

JL: I think the regulatory system in the US is much more mature and proven to be better for entrepreneurs and innovators, very good and reliable for business, and, of course, very favorable for investors, especially long-term investors like us. Speaking of the regulatory risk, I would also like to point out the risk of not taking actions on some of these long-term issues. Because when we talk about cybersecurity, antitrust, all kinds of social issues—these are not specific to China. These are very common issues in every part of the world. The US is trying to address them. Europe is trying to address them.

If other countries are not able to take on these issues in sensible and timely ways, they will have challenges, and their long-term economic development eventually will affect the return of long-term investors like us. Also, there’s a question of how much regulatory risks have been discounted in the current stock crisis. In the past several months, obviously, the market has been more alert toward the regulatory risk in China. Maybe that’s sufficient, maybe that’s over-reaction. But in other parts of the world, in other markets, maybe the regulatory risks have not yet been fully discounted yet.

FR: How about it, Andrew? Are the price changes in Chinese equities causing you to be more interested in Chinese equities? Or does the scope of the regulatory risks cause you to be more cautious?

AW: It’s a tug of war. On one side, risks have risen, I think. Or the awareness of risks that were there have crystallized. And we don’t know exactly how much more is to come. My suspicion is that there might be a slowing down, but that’s not for sure. On the other hand, there’s definitely more risk discounted than before. So, on the one hand, you’ve got maybe some concerns about future margins, future growth for some companies. On the other, a lower price.

The International Equity strategy, which you and I are Co-Portfolio Managers of, has been underweight China for the past several years as China has risen in terms of the index weight. And that was modestly negative for us when Chinese stocks were going up. It’s been favorable for us as the market has declined recently. And so, we are looking at whether to add new securities or add to some existing securities that have become cheaper relative to fair values. My natural tendency is to be fearful when others are not, and to be less fearful when others are more. So, I would say, I would be looking to reduce that underweight on the assumption we find some securities that are over-discounting risk and under-appreciating long-term growth and profitability.

FR: Craig, you were chafing under the limit of 35% in China. I happened to check this morning. China is now less than 35% in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Are you more inclined to buy? And will you go overweight now than you can?

CS: We are doing the same thing we’ve always done—looking for quality-growth companies at reasonable prices. Andrew said it very well: It’s a tug of war. And it’s always been like that. Some of the changes that have come around the last few months have made it a little more challenging, but our reaction has been to purchase more Chinese equities. We had five purchases in the second quarter. Four of them were in China in response to 1) new ideas from our analysts, and 2) lower share prices and valuations. This is what we do. It’s not always easy. Sometimes it’s not fun.

Some of the changes that have come around the last few months have made it a little more challenging, but our reaction has been to purchase more Chinese equities.

FR: Pradipta, you have no choice but to invest in Chinese companies in the Chinese Equity strategy, but you do have choices between industries. Are there industries at this stage that you would avoid, other than the obvious one of the tutoring industry?

PC: Picking up on the ESG front, we’ve always considered ESG risk in these companies, and I think the social element has to be increased.

When I look at it through that lens, there are sectors like the property development sector, for example, where after the recent Politburo meeting there was talk about how housing is for living, not for speculation, right? Those kinds of comments give you hints that there are more regulatory strictures to come.

FR: Isn’t Harding Loevner generally biased against property development in the first place?

PC: Yes. So, that’s an industry thankfully we don’t own right now. We don’t want it because of quality and growth reasons, obviously. But then, there is another layer of risk that is coming.

FR: Confirming our bias against it.

PC: Yes. But I would also be very cautious about some of the other sectors where we do have stocks, like Health Care. Under the social equality principle and health care affordability for all, I would think—especially generic drugs, which have lower content in terms of technology and innovation—those probably are at risk of further price compression. Then the anti-trust regulations are breaking down barriers, which are changing industry structures from what we knew them to be a year back.

So, from the point of view that Andrew talked about earlier, the Porter structure is changing. We need to re-look at the growth cases. We need to re-look at the competitive advantage cases for some of our companies. And then act accordingly. Optically, the valuation might have become better. But in some cases, the valuation may not have become as much better as it seems.

FR: Jingyi, are there industries you have increased your aversion to in the last couple of months?

JL: The short answer is no. I don’t see any sort of a wholesale attitude change to any particular industry. That said, we need to look at our business from an ESG angle, especially the social angle, in a deeper and more profound way. We need to try to understand the social implications of their business models and to think about whether there’s any very profound social impact we should be aware of.

You asked about the sectors to avoid. I should point out that higher regulatory standards, or standards for social awareness, could also open investment opportunity in companies that are more aware of those issues to begin with, or with the management teams who can do a better job to adapt to these kinds of requirements, or even companies that provide solutions to address some of the social issues. So, all these regulatory changes may also provide us some interesting new investment opportunities, again using our fundamental Porter lenses and ESG frameworks.

FR: I’m going to sum up, and then, we can get to questions from outside. As Andrew pointed out, we explicitly try to assess regulatory risk in the framework of our research process, through the lens of Porter’s Five Forces. And I think importantly, we do have a culture of debate between analysts—between PMs and analysts, between people who know a lot about China and people who have questions about China—and that culture of debate is a very active part of getting to the underlying truth of what’s going on. The third thing I would point out is that the insistence on diversification in all our investment strategies is something that we are deeply wedded to, as I alluded to at the start when discussing the nature of pre-commitments.

I think ESG is getting a new take that is reinforcing our belief that ESG risks are exactly that, and that the way we’ve embedded ESG analysis into our research structure is the right way to approach the whole set of issues. And then, finally, the price declines in these Chinese equities are giving us a chance to reassess each of the companies within our coverage and ascertain whether future returns are higher because the prices are lower, or the prices are accurately reflecting the new risk. That is a company-by-company and stock-by-stock issue that we are actively engaged in right now.

Audience Question: Can you comment on your current views on VIEs and whether the VIE structure is at risk due to some of the regulations and regulatory changes that have come out of China?

FR: I’ll take that one. VIEs, for those who don’t know, are variable interest entities, which are special purpose vehicles that connect US-listed stocks to domestic Chinese businesses through holding companies and some third country and equity swaps to get the returns connecting the two.

We have long viewed VIEs as a precarious legal structure and, therefore, set limits on how much each strategy could invest in VIEs. Nothing in the current imbroglio of regulatory shifts affecting the share prices of companies utilizing VIEs has made us see VIEs as more risky or less risky. In our view, the precariousness lies in the legal structure itself and our limits on VIEs are not changing.

I would say that there is debate internally about whether Chinese authorities have, in some sense, blessed the VIE structure by allowing what are called CDRs—a Chinese equivalent of ADRs whose primary listing is a VIE—to be listed in domestic exchanges in China. While that gives some comfort, it’s a regulatory rather than a legal backing, in my view, and in the view of our legal experts.

I was also troubled by statements out of the recent Politburo meeting. I only get translations, but one of the statements was that “the Politburo is going to improve overseas listing supervision.” We’ve had the phrase “rectify” applied to several of these industries where regulatory changes have occurred. I’m uncomfortable with this word “improve” because it sounds a lot like rectified, which could be damaging. Jingyi, how would you characterize that phrase? What do you think it means?

JL: Yeah, I’m really reading the tea leaves here, but my understanding of this phrase, which is very interesting, if not important, is that the policymakers still understand the necessity of a VIE structure …

FR: In order for Chinese companies to raise capital abroad?

JL: To raise capital. They fully understand the historical background going back in the early 2000s. There are long debates inside China on what to do with the VIE structure, but, after all these years, I do not think they have taken a hostile view on this.

The reason that we have a change is they are always worried that some companies may abuse the structure. And that’s why they think they need to take a more active role to supervise Chinese companies that use it to get listed. It’s fine to use that structure, but it’s not fine in their eyes to use it to circumvent some of the regulatory frameworks that are in place to prevent some companies from doing certain things. That’s my understanding.

Audience Question: Why invest in China at all?

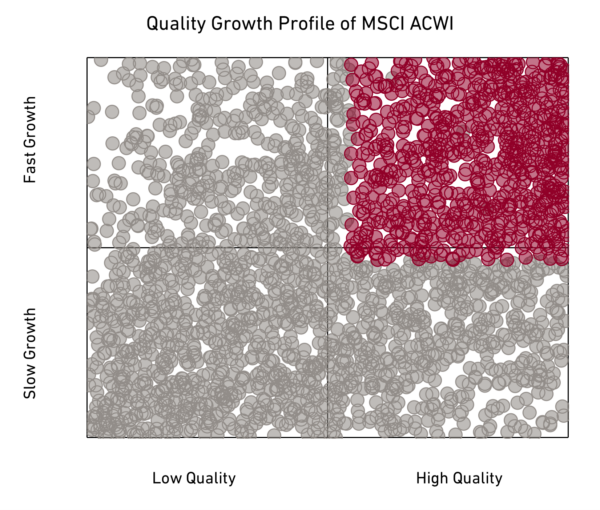

AW: We’ve invested in a lot of risky places and we’ve made money in a lot of risky places over the decades. As we said, we don’t get paid for being comfortable. China represents roughly 10% of the international index. Our analysts have found over 50 companies that meet our pretty high standards for quality and growth.

So, we think there are companies out there that are attractive, not just relative to other Chinese companies, but on a global basis. That is the opportunity. And then there’s dealing with the risks of it. That’s something that we’ve done for decades. We very rarely rule out any country’s securities. As I mentioned earlier, we may require higher returns to compensate us for the risks that we take, and we are intelligent about diversifying those risks as well.

We think there are companies out there that are attractive, not just relative to other Chinese companies, but on a global basis. That is the opportunity. And then there’s dealing with the risks of it. That’s something that we’ve done for decades.

PC: If I may add, as a market, China is massive with huge consumption opportunities that are transforming in a significant way. But, relatively speaking, there are pockets where the risk is lesser and much more aligned with what the government is trying to achieve in terms of its national and overall social objectives.

The massive production base in China is also transforming through the increasing penetration of automation. This entire area is one where we find very, very high-quality companies which are rapidly growing. Electric vehicles and their value chain are another area related to that and one which is very well-aligned with the government’s carbon neutrality goals. China has the largest value chain as well as some of the biggest consumer demand for these cars.

So, there are those pockets that continue to be very, very high-growth and have very high-quality companies that meet our requirements and are very attractive from a long-term point of view. Especially in a country which is right now going through a massive transformation.