Two recent research papers suggest the rise of passive investing is indeed reshaping market dynamics, placing greater pressure on active investors and changing the nature of liquidity and price discovery.

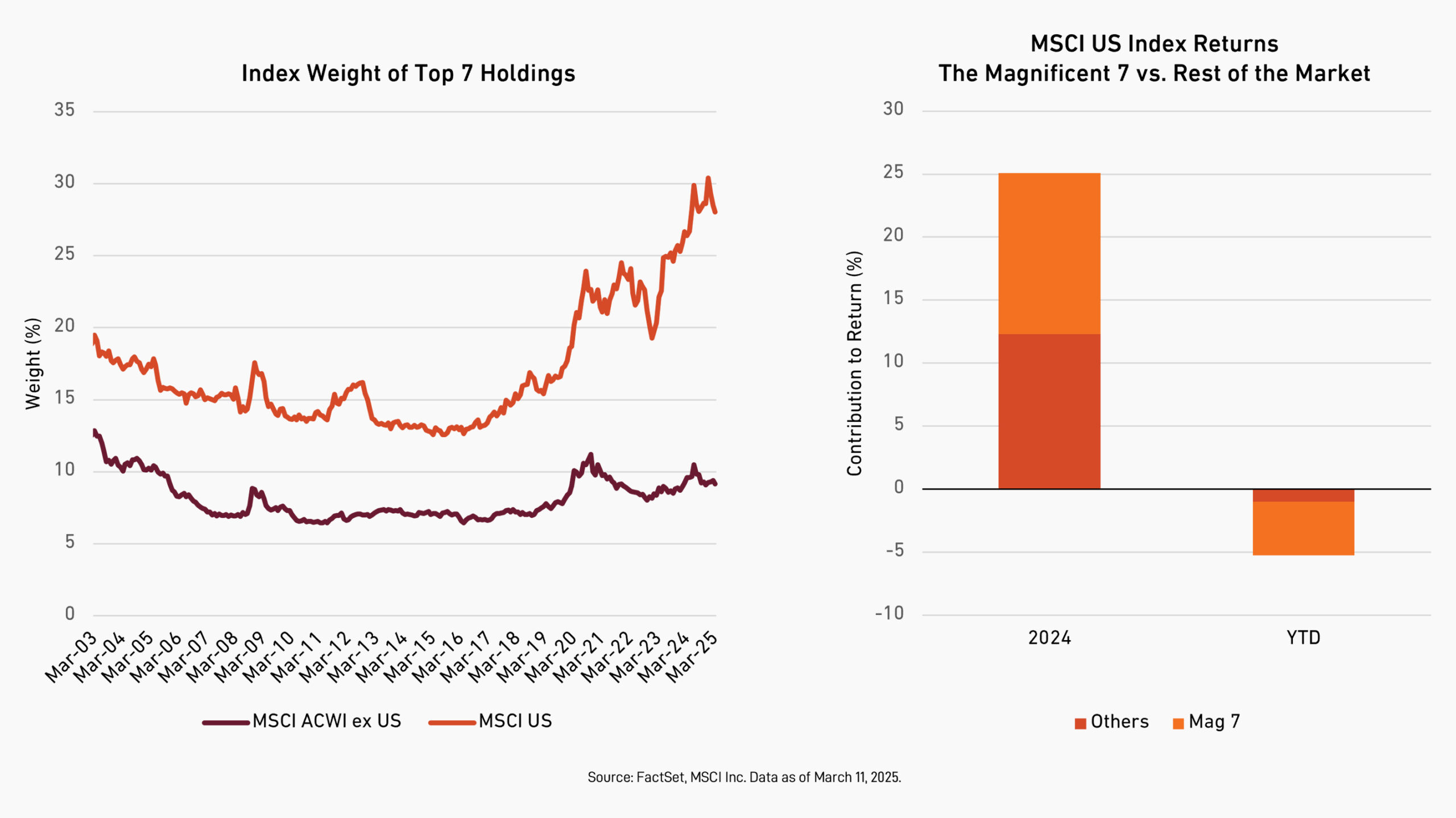

The first paper by Jiang, Vayanos, and Zheng, “Passive Investing and the Rise of Mega-Firms,” develops a framework in which two types of investors, “experts” (active traders) and “non-experts” (passive traders), interact in a market with growing passive flows. Experts make unconstrained investment decisions based on expected returns, while non-experts simply hold an index portfolio. The model posits that rising passive inflows disproportionately benefit the shares of the largest firms—typically those already subject to strong investor demand or overvaluation. Because large-cap stocks are a larger part of indexes, passive funds naturally allocate more capital to these stocks, inflating their prices and, paradoxically, increasing their daily volatility. Consequently, the active trading experts become increasingly hesitant to short or trim positions in overvalued large-cap stocks, as such strategies grow riskier in an environment dominated by persistent non-expert passive inflows.

The authors test these predictions using more than two decades of data on S&P 500 mutual funds and ETFs. They find that during quarters with significant passive inflows, the largest index constituents experience the biggest price gains and elevated volatility. And firms that join the S&P 500 see share price increases that are positively correlated with the size of the company, reinforcing the idea that passive investing amplifies the advantages—and fragility—of mega-cap stocks.

A separate paper by Haddad, Huebner, and Loualiche, “How Competitive is the Stock Market? Theory, Evidence from Portfolios, and Implications for the Rise of Passive Investing,” investigates how competition among investors shapes stock prices, particularly when the behavior of one investor group (such as active investors) shifts toward passive strategies. Departing from traditional models of market efficiency—where reduced trading by some group of investors is assumed to be completely offset by increased trading from others, leaving prices unaffected—this study explicitly incorporates “strategic responses” into its demand framework. In the author’s approach, an active investor’s sensitivity to price (elasticity) depends not only on a stock’s valuation but also on how aggressively other investors trade.

To test their model, the authors looked at data on institutional ownership in US markets from 2001 to 2020. Because investor behavior and stock prices interact, the researchers needed a way to separate cause from effect. They achieved this by focusing on characteristics of investors—such as the overall size of their asset bases and which stocks they’re permitted to buy—that influence their trading but aren’t directly shaped by short-term price movements. Using this approach, the authors find that when those investors shift to passive strategies, active investors respond only partially, by becoming somewhat more aggressive traders. This has left markets roughly 11% more “inelastic,” meaning stock prices react more strongly to buying or selling pressures.

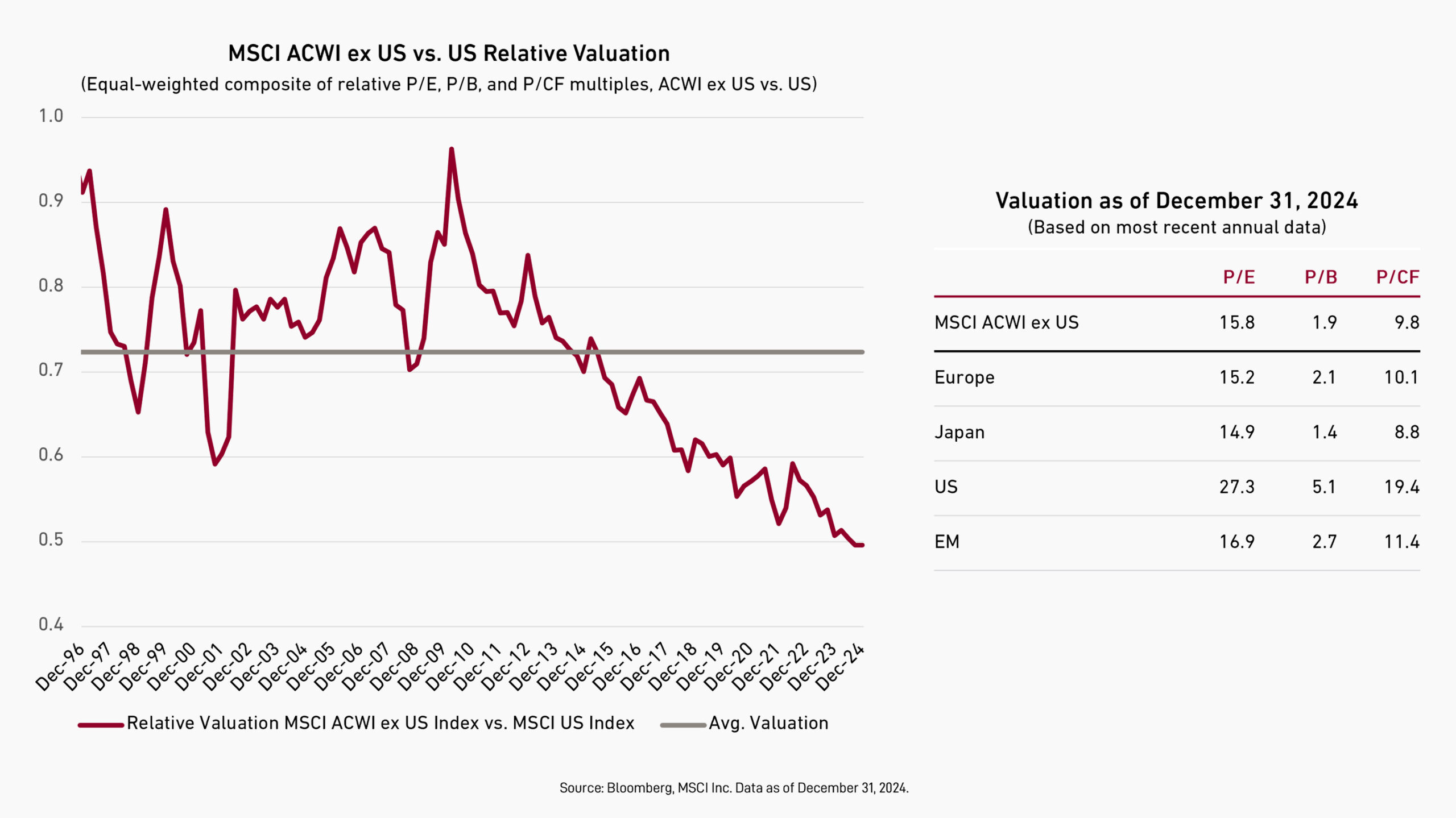

This decline in market elasticity has important implications. As markets become less elastic, modest changes in capital flows can trigger outsized price movements—amplifying volatility and weakening the connection between prices and fundamentals. Large-cap stocks are especially exposed: their sheer size makes them indispensable to index replication, forcing them to absorb a disproportionate share of passive flows, which dulls the influence of fundamentals.

Although some active investors do adjust their behavior in response to rising passive flows, their ability to fully offset the loss of active trading is limited by capital constraints. The notion that investor competition automatically ensures stable and efficient pricing looks increasingly outdated.

These findings make clear that passive investing has shifted the playing field for active managers. As index-driven capital increasingly influences pricing and volatility—particularly among large-cap stocks—certain portfolio traits carry heightened risk. Concentrated positions, large sector or country tilts, and risk frameworks that don’t account for this changing landscape may all be more vulnerable.

Concentrated portfolios have long been held up as a mark of investment conviction. The logic is straightforward: if a manager has a genuine edge, concentrating capital in fewer positions allows for deeper analysis and a portfolio that more precisely reflects their views. With ten or twenty holdings, it’s possible to understand each company intimately—its business model, management, financials, and strategic risks. That level of familiarity is more challenging as the number of holdings increases.

But high concentration also exposes portfolios to single points of failure. That failure might come from a specific company, a common theme or sector, or a broader market shift. And when markets are being shaped more by mechanical flows than deliberate trading, the timing and force of those failures become harder to anticipate. More diversified portfolios, by contrast, help mitigate this exposure. They don’t eliminate risk, but they spread it more widely, reducing the likelihood that any one misjudgment—or market distortion—proves catastrophic. In an environment where pricing is increasingly shaped by factors beyond fundamentals, that cushion matters more than ever.

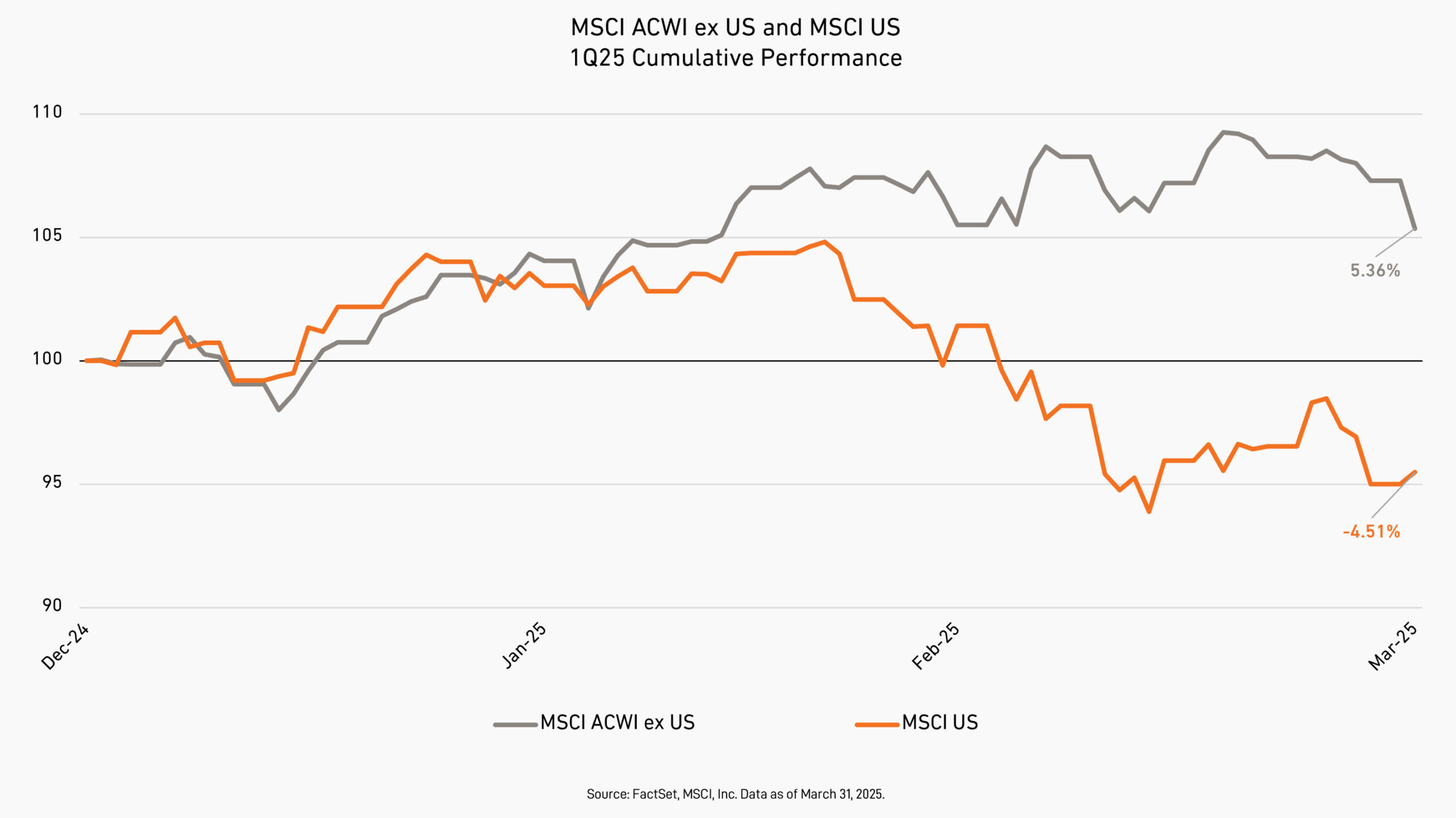

Just as concentrated portfolios heighten exposure to individual company risk, large active country or sector weights also magnify vulnerability. When a growing share of capital flows is driven by index weights, outsized positions in major regions or sectors may deliver performance that reflects strong flows more than manager skill. This can create a false sense of confidence: managers overweighting popular areas—such as US tech or global megacaps—may benefit from flow-driven gains, only to face abrupt reversals when flows moderate or rotate.

These risks are amplified by growing price inelasticity, which weakens price signals. Fundamentals remain critical, but they increasingly compete with mechanical, valuation-insensitive flows. In this environment, large top-down sector or country exposures—whether driven by macro views or the cumulative effect of bottom-up positioning—can have less predictable results. With diminished market responsiveness, even modest sentiment shifts or index rebalancing can provoke outsized price movements. Such exposures may still have a role in active portfolios, but they require a higher bar for inclusion—not just because fundamentals change, but because the market’s response to them has become less stable.

Evolving risks means active investors must rethink not just where they look for returns, but how they manage the risks that come with pursuing them. The old playbook—making investment decisions first and applying risk controls afterward—is increasingly inadequate. When pricing is sensitive to flows, not just fundamentals, and when volatility can be caused by mechanical rebalancing rather than new information, risk management is no longer just a safeguard, it’s part of the thesis. Embedding risk considerations into position sizing, diversification, and liquidity assessments is not being cautious for its own sake—it’s recognizing that the pathways through which risk manifests have changed.

Paradoxically, a more distorted, less efficient market should in theory offer more opportunities for active managers. As Cliff Asness argued in “The Less Efficient Market Hypothesis” market inefficiencies may grow, not shrink, in a world where fewer fundamental investors are actively seeking mispricings. But capitalizing on these opportunities will likely require a different toolkit than the one that worked in a more stable, fundamentally anchored environment. Concentrated bets and implicit top-down exposures may no longer offer the same payoff they once did. Instead, active managers may need to rely more on diversification and a closer coupling of investment insight with risk awareness. In a market shaped increasingly by flows, generating alpha will depend not just on being right—but on being resilient.