The following is adapted from our third-quarter report for the International Equity strategy. Click here to read the full report.

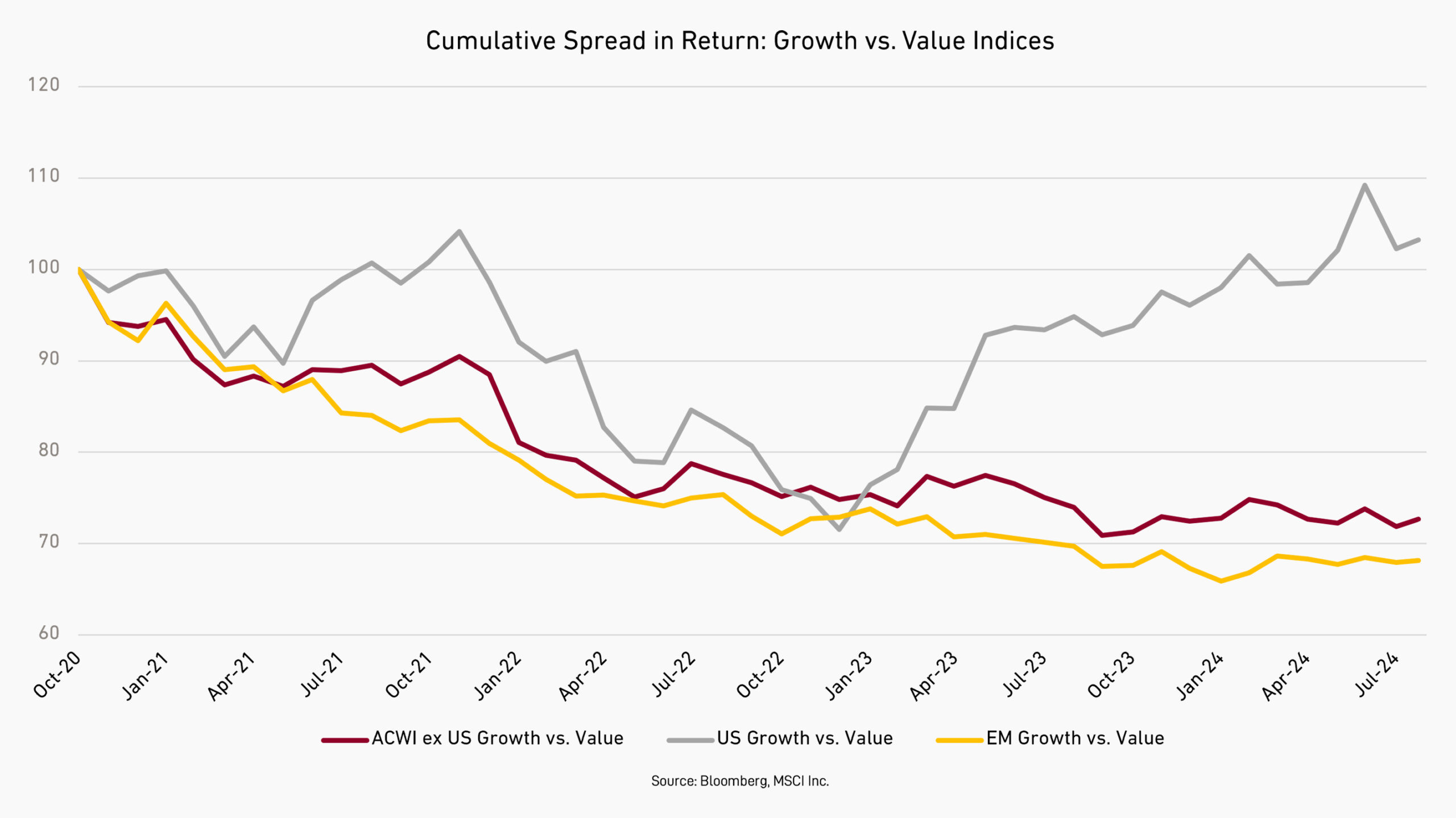

Over the last 18 months, disciplined fundamental investors have been challenged by an episode of price momentum concentrated in a few of the largest stocks in the market. Price momentum refers to a phenomenon where securities whose prices have risen are more likely to keep rising in the short run, while those that have fallen are more likely to experience further declines. The concept of momentum has garnered sufficient adherents to secure its place in the pantheon of portfolio analytics and inspire the creation of numerous indices and ETFs designed to exploit it.

We have deliberately resisted incorporating the momentum factor into our investment process for several reasons. First, simple price momentum does not provide a fundamental basis for making investment decisions. Serial correlation of share price changes has, at best, a weak connection to the underlying business you’re investing in, and nothing to do with what it is worth. Second, momentum investing is literally “chasing” stocks that have already gone up or outperformed (or selling those that already went down or underperformed). This approach leads to higher turnover and trading costs. Lastly, although momentum investing has shown net positive returns over very long periods, there is considerable volatility in its return path. Momentum works until it doesn’t, and when it doesn’t, all the gains you made can be reversed more quickly than you can exit the market. This whipsaw effect makes momentum investing much harder to stomach in practice than it appears in theory.

Of course, there are cases when stock price momentum is linked to company fundamentals. Apple is an example where a profound and structural change is harnessed by a company over a long period, leading to sustained profit growth and extended share price appreciation. Such dynamics are possibly at play in the recent fever for companies linked to the development of artificial intelligence or weight-loss drugs. But such cases are rare and most of the time investors tend to overestimate the number of transformative changes that will actually materialize.

Momentum in the markets is often driven less by fundamentals and more by the fear of missing out (FOMO). In our experience, the FOMO response is most acute when it’s most dangerous—near the peak of market trends, or worse, an investment bubble. Investors who hold the winning stocks are happy to hold on, while those who don’t quickly feel the pressure of “missing out,” amplified by the constant media coverage that acts as free advertising for these market leaders. Passive investors inadvertently pour more capital into these heavyweight stocks in ever-increasing percentages, further amplifying their impact. As a result, the momentum behind these stocks grows ever stronger, and they come to dominate index returns. All (human) investors who measure themselves against a benchmark index feel drawn to jump on the bandwagon. We suspect that FOMO has been a significant element contributing to some of the most damaging drawdowns in the performance record of momentum investing, and we expect it will likely feature in some doozies to come.

We are well aware of the behavioral pitfalls in investing and use a variety of tools to promote objectivity in decision-making. But we can be just as susceptible as other investors to the temptations of momentum. To stiffen our resolve, we’ve made pre-commitments in the form of absolute limits in our risk guidelines, which are primarily aimed at enforcing diversification in our portfolios, but secondarily act as brakes to curb our enthusiasm.