Walmex caught a break in December. The Mexican retailer, majority owned by US giant Walmart, received only a minor penalty–what amounted to about a US$5 million fine as well as some new restrictions and ongoing oversight—after a four-year investigation by Mexican regulators into the company’s business practices. Walmex’s stock rose as it appeared a severe penalty in the billions of dollars had been avoided.

And yet, Walmex plans to appeal the verdict by Mexico’s antitrust watchdog, the Federal Economic Competition Commission, or Cofece. To understand why the company wasn’t happy with a minor financial burden—Walmex earned US$657 million in the third quarter of 2024 alone—you need to understand how retailers such as Walmex make their money.

The investigation began after Chedraui, the third-largest retail chain in Mexico, accused Walmex of abusing its market power, using its size to coerce suppliers into giving it better prices and terms than they could to competitors, especially smaller ones. A Reuters story amplified the claims of pressuring suppliers, finding that some of those suppliers removed their products from Amazon as a result of Walmex’s pressure. Cofece’s investigation concluded that Walmex abused its position over the course of 13 years and broke anti-monopoly laws in the process.

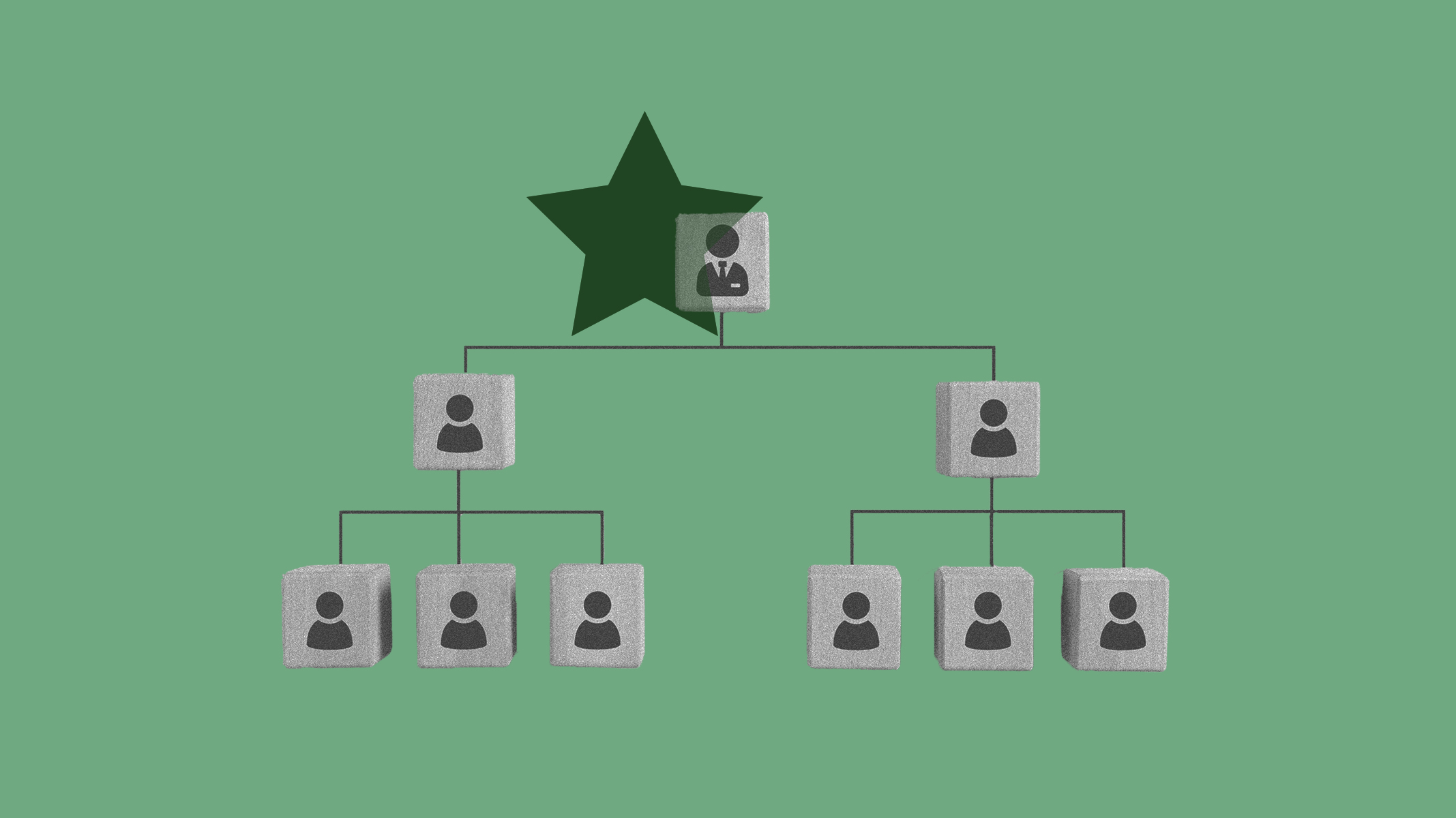

The common assumption with big retailers such as Walmex is that their power and profits are a result of their scale and ability to lower prices on products that will attract and keep customers. And that is true and well understood. But what is not well understood is how its scale gives the company that power. Retailers don’t make their money on consumers. They make it on suppliers.

There is an intricate game between retailers, suppliers, and customers. Customers have bargaining power with retailers, because they will go wherever prices are the best. Therefore retailers have little bargaining power with their customers—but can have a lot of bargaining power with suppliers. Successful retailers become the conduit to customers and therefore gain an advantage over their suppliers. Retailers use that bargaining power to force terms from suppliers that advantage the retailers, and offset the retailers’ weak bargaining power against fickle buyers. What Cofece concluded was that Walmex was abusing that power.

The Cofece ruling imposed a ban against some of Walmex’s practices, such as retaliating against suppliers based on their contracts with other retailers. That should raise the bargaining power of suppliers against Walmex. The impact, though, is hard to predict. If the ruling stands, it would effectively reduce Walmex’s competitive advantages, which would hurt the bottom line. That won’t be an issue if it wins on appeal, though it will likely be several years for that to play out.

In the meantime, there are two wrinkles. For one thing, Cofece, in its oversight role, will determine whether the company is violating the ruling. For example, the ruling does not appear to ban volume-based discounts. But if Walmex demands a 50% discount from a supplier on, say, 10 million units of an item, will that constitute a violation? For now, only Cofece gets to answer that question. Moreover, the ruling applies specifically and only to Walmex. In effect, Cofece is raising the bargaining power of suppliers…against Walmex only.

That is the real reason Walmex is appealing the ruling rather than just paying the small fine and moving on. Because ultimately what makes a retailer successful is the leverage it holds over its suppliers, not its customers.