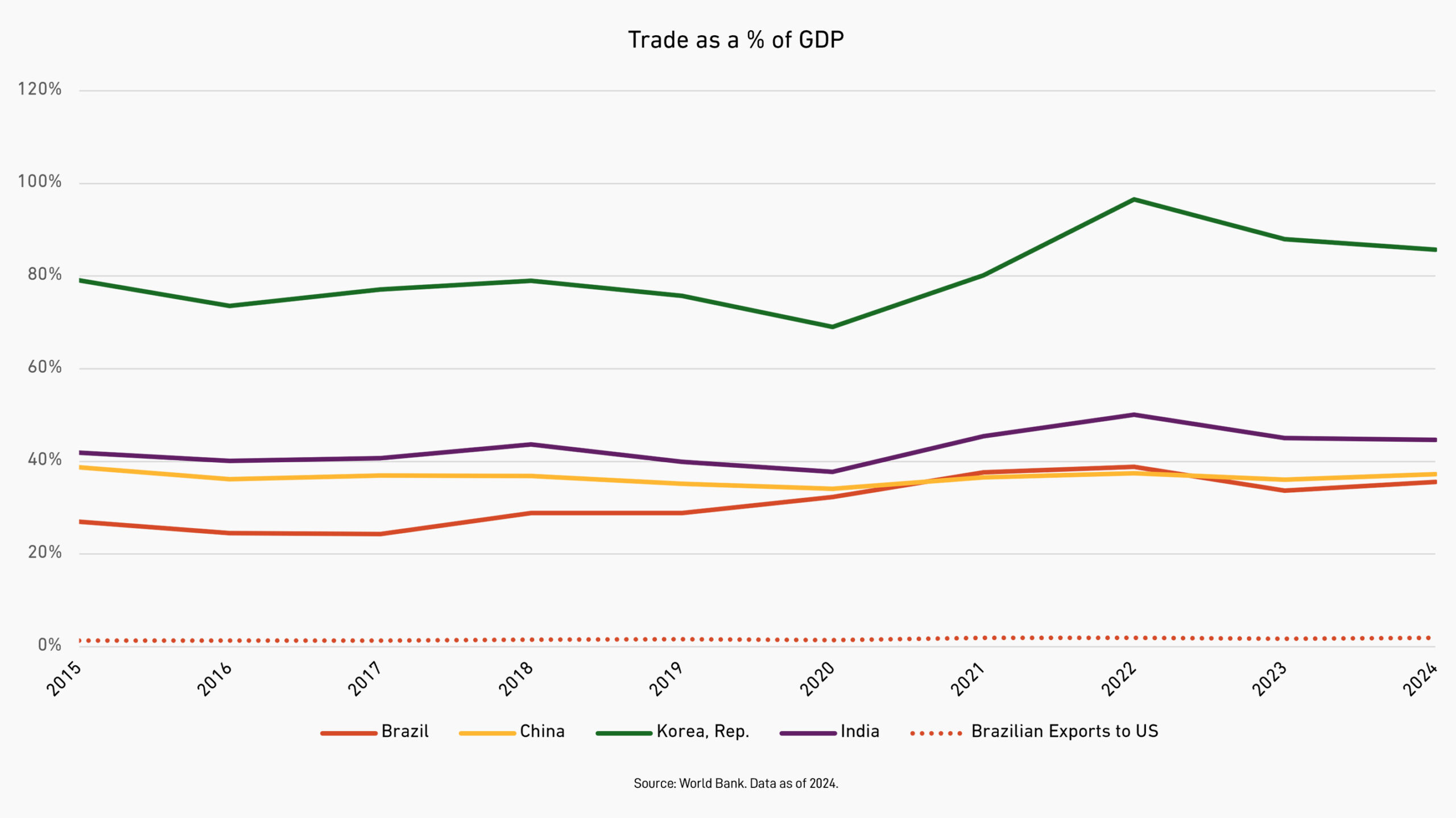

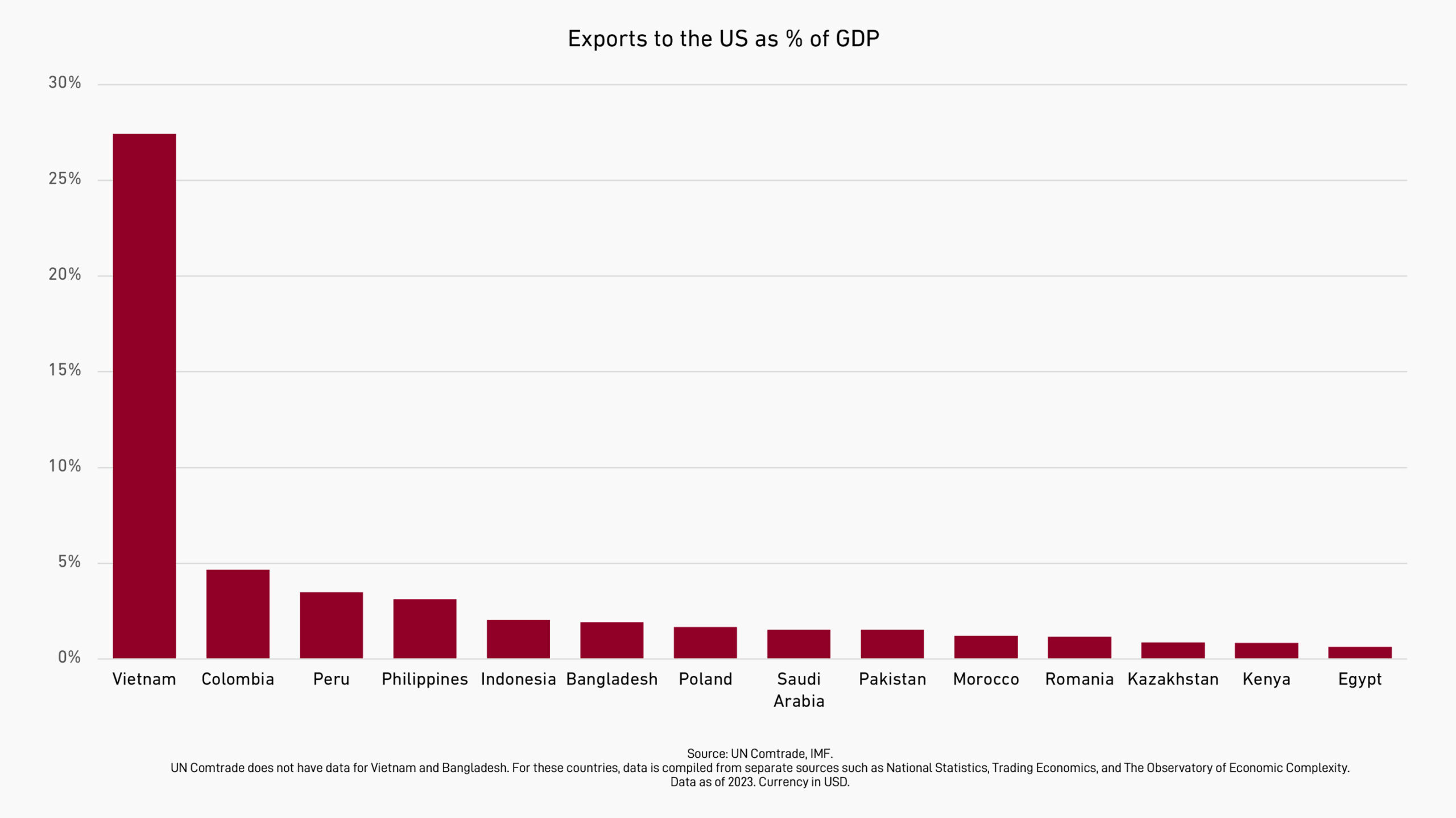

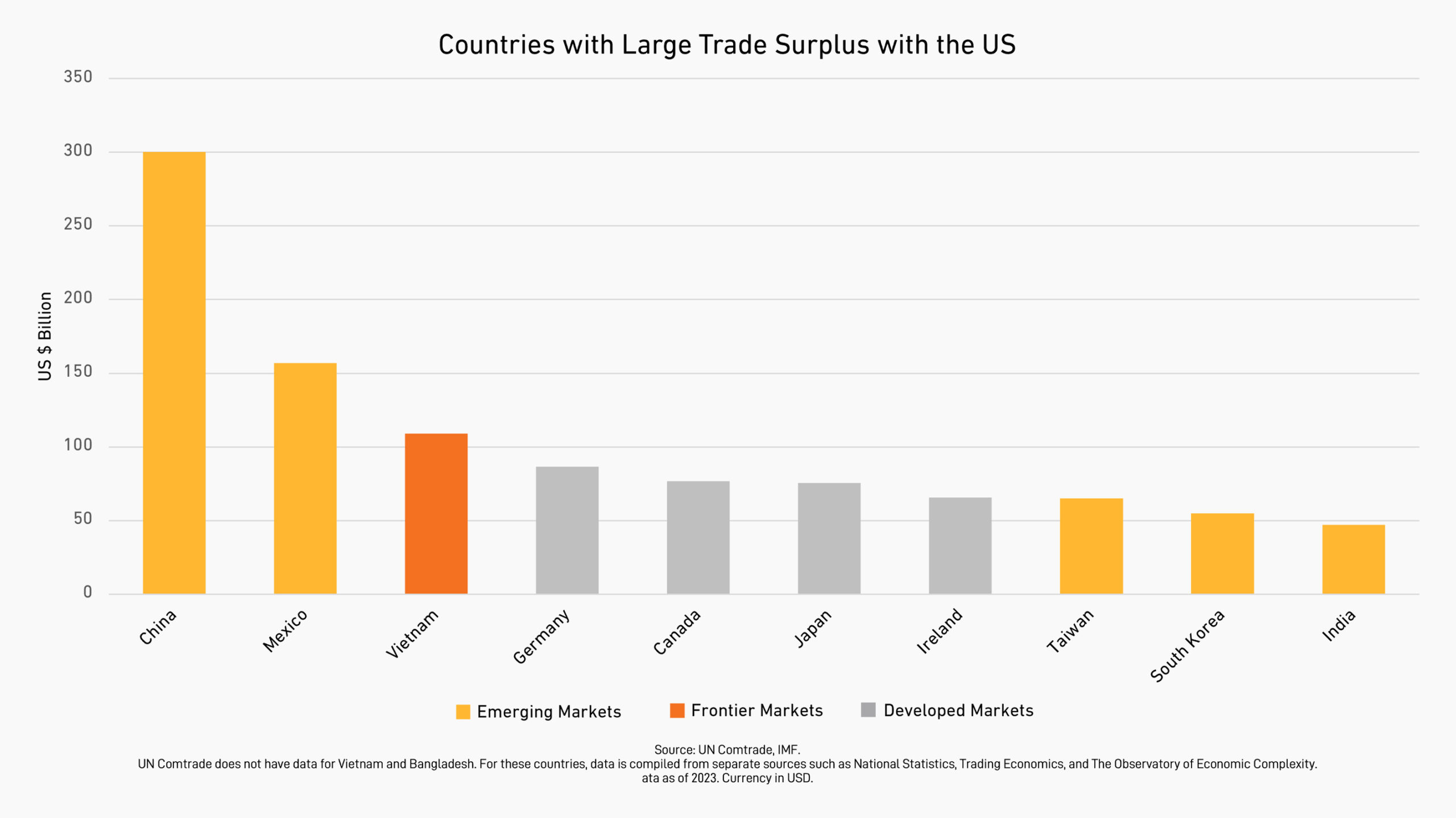

President Donald Trump’s trade wars have roiled global markets. Recently, he threatened Brazil with a 50% tariff unless the country drops an investigation into its former president. But the US trade war with the rest of the world hasn’t stopped trade. Indeed, for Brazil, its trade has increased since Trump’s first term, as seen in the chart above. Partially that is because Brazil’s exports to the US are only about 10% of its total exports and account for less than 2% of the country’s GDP.

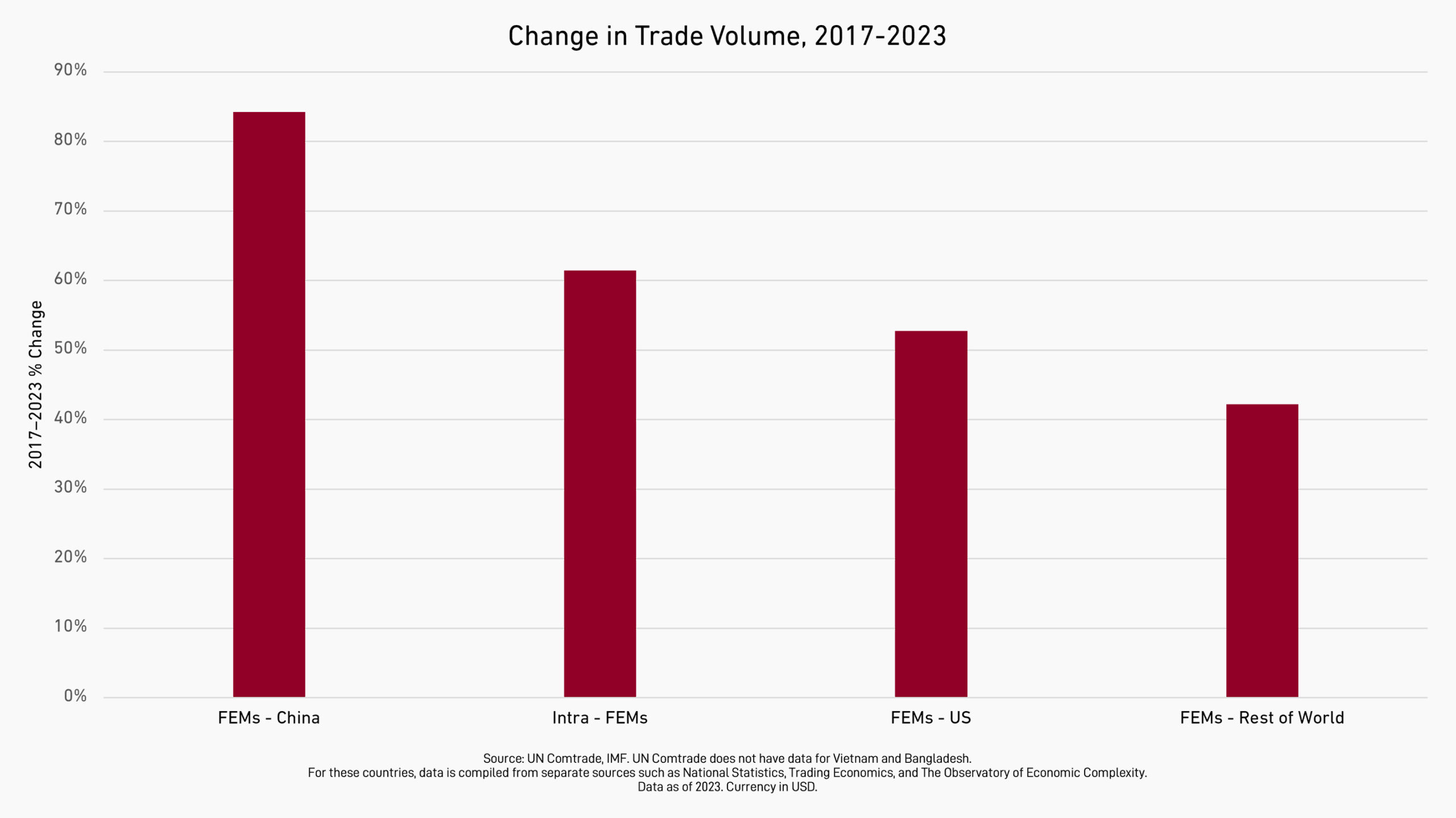

Most of those exports are commodities such as oil, iron ore, beef, and coffee, all of which can easily be sold to other countries. And that is what has been happening. In fact, companies in Emerging Markets (EMs) around the world have responded to Trump’s trade wars by turning to other EMs as a replacement market.

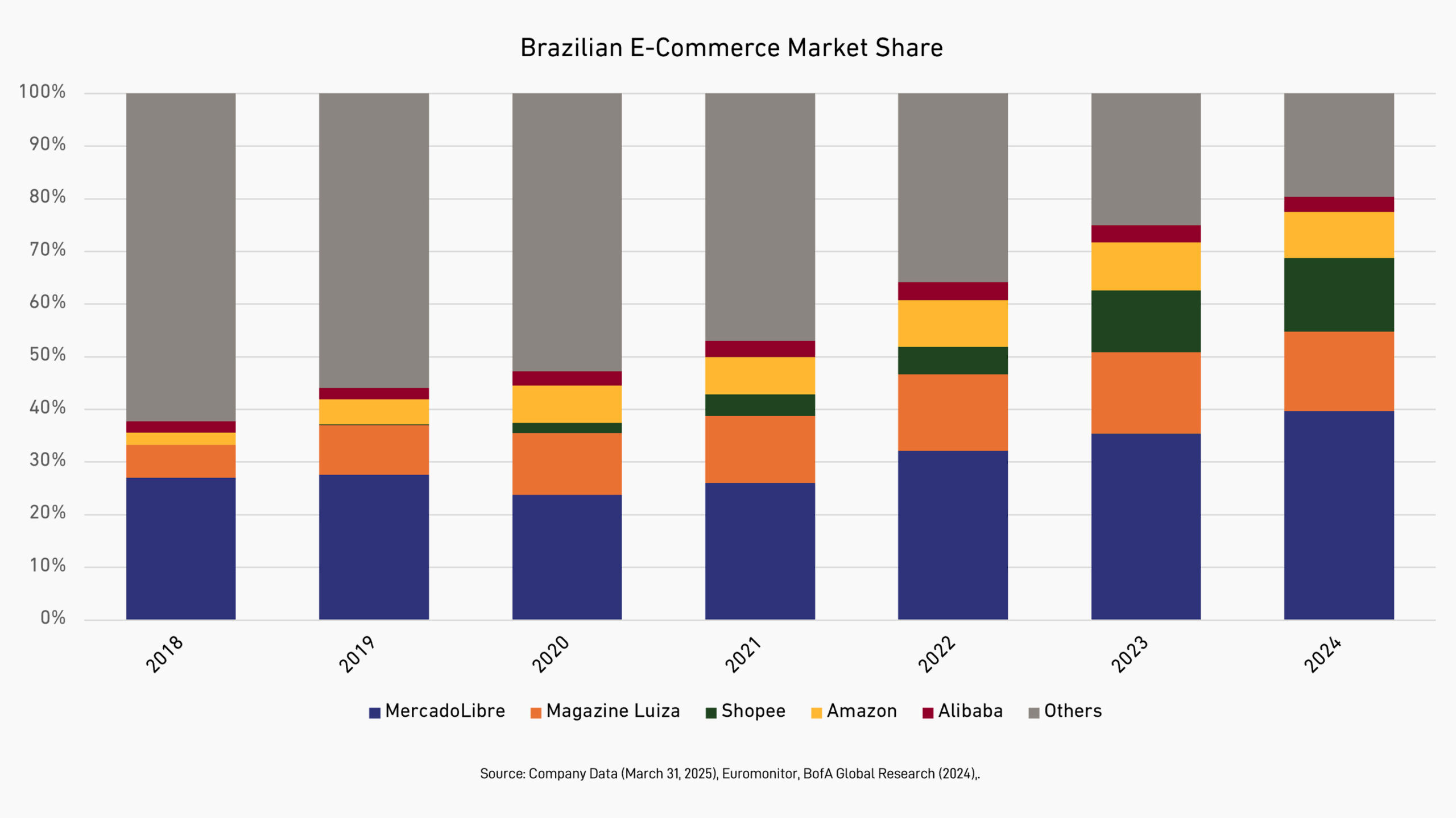

MercadoLibre, Brazil’s ecommerce champion, shows the trend in both directions: It was actually founded in Argentina in 1999 and today operates in 18 countries across Latin America. It launched in Brazil in 2001 when it bought the Brazilian subsidiary of European online auction site iBazar. Over the last decade, since Trump’s trade wars started, the company has stepped up its presence in Brazil.

Other e-commerce firms from Asia such as Sea’s Shopee and Alibaba’s AliExpress are also committing significant capital to tap Brazil’s vast consumer market and the opportunities the country offers in high-margin industries that result in strong returns on invested capital. For MercadoLibre, AliExpress, and Shopee, the increased competition could lead to an increase in adoption, which could help those three and hurt smaller platforms and retailers. For Brazil, the fresh investment helps underscore it as an attractive destination for businesses while also forcing international companies doing business there to become more competitive to meet both the opportunities and challenges of a new, more global marketplace.