Harding Loevner’s Tim Kubarych, David Glickman, and Patrick Todd discuss the implications of the greater use of buyer power within the global pharmaceutical industry.

The average annual profit margins of the world’s 25 largest pharmaceutical companies fluctuated between 15% and 20% from 2006 to 2015, while the average margins of their US non-pharma peers fluctuated between 4% and 9% in the same period, according to a report from the non-partisan US Government Accountability Office.¹ But Big Pharma’s outsized profit streak may be coming to an end. Spurred by rising prices and increasing national spending on health care, governments and health insurance companies—the chief buyers of pharmaceuticals (i.e., those who pay for them on patients’ behalf)—are pressuring pharmaceutical companies to lower their prices.

“In many countries around the world, we’re seeing buyers exercise their bargaining power more heavily,” says Health Care Analyst David Glickman, CFA. “There’s a perception that they’re no longer getting sufficient value for money.”

If buyers continue to exert their power, many drug makers could see their profit margins drop, says Glickman. Their average returns on invested capital have already fallen from roughly 20% in 2008 to 10% in 2018, an indication that industry-wide profits may soon decline.² Even so, pharma companies that make smart resource-allocation decisions around R&D, or that already dominate a therapeutic space, could still be highly profitable in the new competitive environment, he adds.

Change of Heart

Until recently, governments and health insurers had not fully exploited their buyer power over Big Pharma. By and large, buyers accepted high pharmaceutical industry profits against a backdrop of continuous drug innovation that contributed to steadily improving health outcomes. So, what has caused the shift in approach?

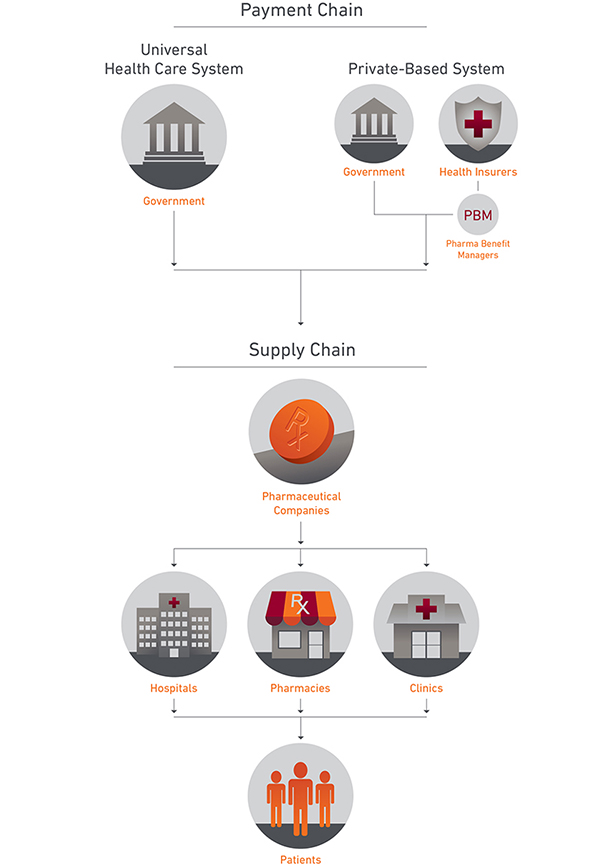

Chain Reaction

The Payment and Supply Chains for Prescription Drugs

In countries with universal health care systems, the government is often the sole buyer of prescription drugs. In the US, which accounts for around 45% of the world’s pharmaceutical market by revenue, the main buyers are health insurance companies (in conjunction with the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), who act as their brokers) and the federal government, which purchases drugs for public programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and the Veterans Affairs health care program.

One of the main reasons is changing demographics. In countries with aging populations, which includes virtually all middle- and high-income countries, per capita consumption of prescription drugs tends to increase, straining governments’ national health care budgets. In the US, characterized by the private market, voters are stepping up pressure on Washington to take action against what they see as spiraling out-of-pocket costs. In turn, the US government is leaning on health insurance companies and PBMs to extract better deals from pharma companies.

Extraction Techniques

Buyers have been flexing their muscles in a variety of ways in their quest to drive down Big Pharma’s prices. In some countries with universal health care, governments are promoting a greater uptake of generics—in addition to direct price negotiations. This has been the policy of Japan, which has seen its national health care spending balloon over the past decade due to an aging population. Low generic penetration has allowed pharmaceutical companies to reap healthy profits from decades-old drugs long after patents have expired. In the short term, Japan hopes cheaper generics will reduce demand for higher-priced branded drugs, thereby lowering government spending on pharmaceuticals overall. In the long term, this policy will likely compel drug makers to increase their R&D budgets in search of new profit-making drugs, thereby boosting innovation in the sector to the ultimate benefit of patients.

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

“Essentially, the Japanese government is telling drug companies they can no longer live off old products. They’ll have to develop new drugs to stay in business,” says Glickman. As the price of generics in Japan has fallen, their penetration by volume has risen from just 20% in 2010 to 66% in 2016, with the government targeting 80% penetration by September 2020. A number of European countries, such as Greece, France, and the Netherlands, are also taking measures to promote greater adoption of generics.

In China, the government last year united pharmaceutical procurement for all the health plans it administers under one umbrella by creating a new agency, the State Medical Insurance Administration (SMIA). One of SMIA’s first acts was to announce that price would be of paramount importance in determining which drugs they include in their formulary, or list of covered medications. As a single buyer, SMIA can provide the lowest bidding drug companies access to a large and fast-growing market, albeit at margins perhaps lower than originally projected.

“Going forward, pharma companies will need to develop new classes of drugs to survive, rather than simply perfecting what’s already been discovered.”

In the US, where generics have already achieved significant penetration, health insurance companies and PBMs are increasingly balking at high prices for drugs that don’t offer substantial improvements over competing products. “Many pharma companies enjoyed high returns on investment for years because they could essentially get away with selling drugs to buyers that were highly derivative of older drugs, making them relatively inexpensive and low-risk to develop,” explains Patrick Todd, CFA, who also analyzes the health care industry. By refusing to pay for high-priced drugs where a cheaper alternative exists—even if that alternative is slightly inferior—buyers are removing a source of low-hanging fruit for Big Pharma, he says. “Going forward, pharma companies will need to develop new classes of drugs to survive, rather than simply perfecting what’s already been discovered.”

Coping Mechanisms

Pharmaceutical companies whose drugs meaningfully improve the “standard of care” in a given therapeutic area can still be immensely profitable—at least for the duration of their exclusivity periods. Yet it’s becoming ever-more expensive to bring a new drug to market—approaching US$3 billion and increasing at an annual pace of 8.5%, according to a 2016 study from Tufts University. And even when highly differentiated pharmaceuticals are approved by regulators, their margins will likely be slimmer due to buyers’ more-assertive posture.

R&D efficiency—especially at the early stages of the drug development process—is becoming more important as a competitive differentiator in this tougher market, says Todd. “In pharma-speak, firms that can create a rich phase-1 pipeline of novel mechanisms of action stand the best chance of maintaining high levels of profitability going forward.”

“I’m as interested in the drugs a company decides to kill—and what they’re learning from those decisions—as I am in the drugs in the pipeline that are showing promise.”

Some firms are deciding to abandon the development of otherwise-promising drug candidates, fearing they won’t be differentiated enough for governments and other buyers to include in their formularies. Sanofi, for example, announced in February 2019 that it would cease work on 25 projects in the research stage and 13 in the drug development stage. Instead, the French drug maker will shift its focus to areas where it believes it is more likely to advance the standard of care. “These days, I’m as interested in the drugs a company decides to kill—and what they’re learning from those decisions—as I am in the drugs in the pipeline that are showing promise,” says Glickman.

Other companies are using Real-World Evidence (RWE) to evaluate the efficacy of their pharmaceuticals already on the market. By conducting these studies, drug companies hope to convince buyers that their high prices, or even increased prices, are justified. While evidence of efficacy has been gathered for decades through long-term medical studies, the ability to track patient health via wearable devices, availability of digitized health records, and advances in data analytics have made it much more cost-effective to obtain.

Yet there’s an important exception. Pharmaceutical companies may be able to retain the upper hand in negotiating the price of a new drug when the current version of that drug dominates a therapeutic space and has a good reputation among doctors and patients. If the new version of the drug is additionally supported by a large marketing budget, drug makers could generate sufficient demand that buyers would be convinced to cough up, even when less-expensive alternatives are available.

As a case in point, Todd and Glickman cite Humira, an immunosuppressive drug developed by US pharmaceutical company AbbVie. Humira, used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, among other ailments, is a clear leader in its therapeutic areas, and has been the world’s best-selling drug since 2013. AbbVie is in the process of replacing Humira with two new drugs: Skyrizi, which has already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and a yet-to-be-named drug currently under review. Both successors stand a good chance of generating high profits, say the analysts, even though they will be little-differentiated from similar drugs launched recently by other drug makers.

Anticipating high patient demand, many buyers have been faster to add Skyrizi to their formularies than rival drugs launched earlier. The other successor drug is also likely to gain quick acceptance from buyers, he says. “AbbVie’s commercialization prowess is among the best in the industry, and their marketing budget for these drugs will be sizeable. Patients will be asking their doctors for them, and doctors will be asking their suppliers for them, so buyers will most likely succumb to the demand,” says Glickman. Despite this, Glickman and Todd predict that the new commercial realities will probably force AbbVie to lower their price points. With drug pricing under the microscope, the rules of the game have clearly changed.

What did you think of this piece?

Contributors

Deputy Director of Research Timothy Kubarych, CFA and Analysts David Glickman, CFA and Patrick Todd, CFA contributed research and viewpoints to this piece.

Endnotes

1“Non-pharma peers” refers to non-pharmaceutical companies in the S&P 500 at the time of the study, which the US Government Accountability Office uses as a comparison group.

2Data from the HOLT database, accessed 07/19/2019.

Disclosures

The “Fundamental Thinking” series presents the perspectives of Harding Loevner’s analysts on a range of investment topics, highlighting our fundamental research and providing insight into how we approach quality growth investing. For more detailed information regarding particular investment strategies, please visit our website, www.hardingloevner.com. Any statements made by employees of Harding Loevner are solely their own and do not necessarily express or relate to the views or opinions of Harding Loevner.

Any discussion of specific securities is not a recommendation to purchase or sell a particular security. Non-performance based criteria have been used to select the securities identified. It should not be assumed that investment in the securities identified has been or will be profitable. To request a complete list of holdings for the past year, please contact Harding Loevner.

There is no guarantee that any investment strategy will meet its objective. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

© 2024 Harding Loevner