Harding Loevner’s Tim Kubarych, Chris Mack, and Jafar Rizvi discuss the implications of the enterprise software industry’s shift to selling applications via subscription.

The rise of cloud computing and faster internet speeds has prompted a major shift in the way businesses buy and run enterprise software from companies like Microsoft, SAP, and Oracle. Before, businesses paid software companies a hefty upfront fee to license the programs in perpetuity. They installed the application on their own systems and maintained the associated data. Businesses then paid additional fees—usually around 20% of the software’s initial price annually—for technical support and bug fixes. Customers had to update their installed software regularly to the latest version, and if the vendor released a major new version, they had to buy another license.

Today, businesses have another option: they can access software via a web browser for a monthly or annual subscription fee. In the new model, commonly known as Software as a Service (SaaS), applications and their underlying infrastructure are hosted “in the cloud” by the software vendor. All updates are included for as long as the customer remains a subscriber, so customers are always using the latest version. SaaS applications, in most cases, do not require download or installation, just login credentials. And they can typically be run from any device anywhere—so long as one has an internet connection.

The market for SaaS-based applications is booming. Companies of all sizes can now rent the programs and computing capacity they need to create documents (Microsoft Office 365, Google G Suite), share files (Box, DropBox), keep track of expenses (SAP Concur, Certify), administer payroll (ADP, Paychex), track technical issues (Atlassian Jira, Zendesk), manage human resources (Workday HCM, Oracle HCM Cloud), track client relationships (Salesforce), and more. The research firm, Gartner anticipates the global enterprise software market—whose growth is mainly driven by SaaS products—will reach US$460 billion by 2020, up from US$310 billion in 2015, and more than 80% of software companies will offer subscription services by 2020.

The shift to SaaS has expanded the market opportunity for software vendors. It represents not only a new product delivery model but also a new business model, notes Harding Loevner technology analyst Chris Mack, CFA. “When companies in any industry change their business model, everything from accounting to competitive strategy can be affected,” he says. “Investors should be looking at individual companies and the whole enterprise software industry with fresh eyes.”

Perpetual License vs. “Perpetual Money”?

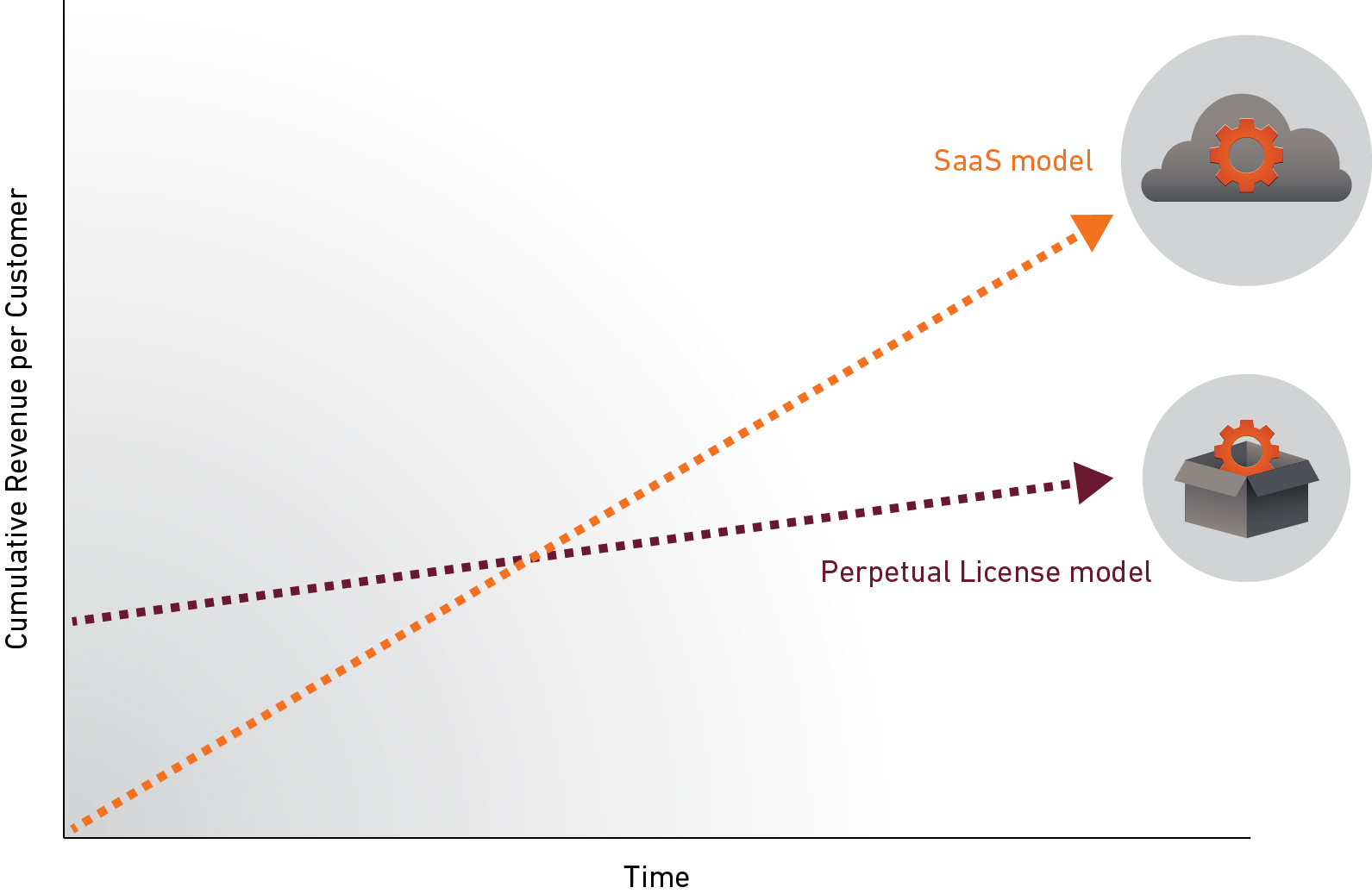

One reason for the subscription model’s appeal is recurring revenues. Though revenue per SaaS customer will be lower in the first year, on a cumulative basis they will eventually surpass those received from perpetual-license customers—provided no more than around 10% of SaaS customers cancel each year.

The Seductiveness of SaaS

In the SaaS model, if an enterprise software company can hold onto its customers, its cumulative revenue per customer eventually outpaces that in the perpetual license model, with the crossover normally occurring in three to five years.

The option of low monthly or annual payments has also expanded the addressable market for many software vendors. Adobe, for example, used to charge around US$2,500 for a perpetual license to its graphics and media software suite, which includes industry-standard applications such as Photoshop and InDesign. Now, would-be users can access the suite for a US$50 monthly subscription. “Suddenly, everyone from large corporations to small graphic design shops and individual freelancers can afford Adobe’s top-class software,” says Harding Loevner technology analyst Jafar Rizvi, CFA. “Think of the effect this has had on their customer numbers.” Not only is there the potential for higher revenue per customer over time, but there is also a potential for more customers.

By hosting the applications, software companies also collect usage data that can reveal what features are used or ignored—valuable information for planning product upgrades. And because all users are running the latest version of each program, software companies no longer have to spend additional money and time developing patches and fixes for older versions, as they were forced to when applications resided in their customers’ data centers.

“If executed successfully, the SaaS model can deliver higher revenues to software makers over the long run,” says Rizvi. A case in point: after effectively switching to a SaaS-only model in May 2013, Adobe’s quarterly revenue has nearly tripled from about US$1 billion to US$2.6 billion in the first quarter of 2019.

Ascending to the Cloud

Adobe’s quarterly revenue, 2005-2019 (US$B)

Source: FactSet.

Caution Required

Not all characteristics of the SaaS model favor software makers’ long-term profitability, Rizvi and Mack caution. Cloud computing, which enabled the SaaS model in the first place, has made it easier for new software companies to enter the market. All components of the “IT stack”—from servers to development tools—can now be rented inexpensively from Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. “To get started these days, all you need to do is rent back-end services from a cloud provider, bring a relatively small team of coders together to develop a new product, and then simply release the software on the internet,” says Rizvi. “The lower barriers to entry explain why we’re seeing a proliferation of new companies in the SaaS space.”

Another risk to software vendors is the ease with which customers can cancel their subscriptions. Typically, unhappy or cash-strapped users can back out with little notice, often with the click of a mouse. As a result, SaaS software companies face greater pressure to improve their products continuously. To be sure, they had to work hard to gain customers in the era of perpetual licenses as well, but once the initial sale was made, they effectively captured that customer’s spending in their specific software category for several years. “Many wouldn’t switch to software B for the sake of marginal improvement, especially after recently buying program A,” Mack says. “In the SaaS model, software makers have no such cushion of safety.”

“Having covered technology stocks for over a decade, I’ve had to shift my thinking about enterprise software companies, particularly when it comes to valuations.”

The concern that large numbers of SaaS users will cancel subscriptions as soon as a competitor releases a slightly superior product is offset by the fact that switching vendors tends to be hard for users in practice. Companies build business processes around the use of an application, train their staff how to use it, and customize it to their particular needs. As a result, they pay a high cost in time and resources when switching to a new product, even if the out-of-pocket costs of switching are low. “There’s still quite a lot of customer lock-in here, more than meets the eye,” says Rizvi.

Valuations in the Clouds

A business in any industry that convinces customers to enter into subscription contracts can potentially achieve a significant rise in average revenues per customer while simultaneously achieving customer growth. As such, the stock prices of many subscription-based companies are often very high, and this is certainly true for SaaS-based software companies. A March 2019 survey of 50 cloud software companies shows an average enterprise value-to-sales ratio of 13.2 compared with the S&P 500’s average of 2.4.

“Having covered technology stocks for over a decade, I’ve had to shift my thinking about enterprise software companies, particularly when it comes to valuations,” says Mack. “Recurring revenue streams are more valuable to me as an investor. So all things being equal I’m willing to pay more for many of these companies than I would have been, say, ten years ago,” he says. “In fact, given the added value that many of these companies are providing their customers, some may even be undervalued.”

Rizvi and Mack note that many of the highest-valued SaaS companies have not generated any profits or free cash flow. In such cases, they say, investors need to look closely at individual companies’ strategies and financial statements to gauge if revenue growth can ever translate into sustained profits. “We see there is a wide range of outcomes,” Rizvi says.

“If costs rise at a faster pace than revenues, adding more and larger customers—or holding on to existing ones for longer—will only make you more successful at losing money.”

The rate of subscription cancellations, or customer churn, is a major factor determining future profits. “If you can only retain customers for an average of three years, and your breakeven point is three years for each new customer, you won’t make money no matter how fast you grow-section,” Rizvi says.

Companies that offer highly differentiated or industry-standard software, or that compete in a product category hard for new rivals to enter, are typically the most successful at sustaining high renewal rates; if few good alternatives exist, customers have little choice but to maintain their subscriptions. High frequency of customer use—say, daily (e.g., team collaboration software) rather than only occasionally (e.g., internal staff surveying software)—is also associated with low churn.

Another profitability factor is the length of a company’s growth runway, Mack says. Companies that sell a wide range of products targeting multiple large markets not only have access to a vast pool of potential customers but also have the ability to cross sell to existing ones. Companies can target small markets first and later expand into larger ones. Salesforce, for example, achieved extraordinarily high growth by selling its customer relationship software to small businesses first and only later expanding its target market to include large corporations.

Still, it’s relatively easy for a company to keep churn low and grow fast if it lowers prices or accelerates spending on customer acquisition, says Mack. “If costs rise at a faster pace than revenues, adding more and larger customers—or holding on to existing ones for longer—will only make you more successful at losing money,” he says. Thus the potential for a software maker to increase its profit margin while it expands is a third factor investors must consider when assessing a company’s potential profitability.

Pursuing high growth, even if expensive in the short term, might not be problematic if a company has a clear strategy to increase prices or lower costs once it reaches a certain size. “Raising prices is easier once you become a well-known brand and have a long positive track-record of customer satisfaction,” says Mack. Scale can also help lower sales and marketing expenses, which in the enterprise software industry can be a large portion of a company’s overall costs. Some companies have been able to reduce marketing expenses as they gain increasing number of customers through word-of-mouth recommendations. Finally, larger scale allows research and development costs and the substantial fixed-cost component of product support to be spread over a wider revenue base.

The point here is not to paint all SaaS companies with the same sanguine brush. “If a SaaS company can figure out a way to achieve high growth while keeping churn low and increasing its margins over time, I don’t mind paying a high price to own a stake, even if they are not yet profitable,” says Mack. “The devil, of course, is in the details.”

What did you think of this piece?

Contributors

Deputy Director of Research Timothy Kubarych, CFA and Analysts Christopher Mack, CFA and Jafar Rizvi, CFA contributed research and viewpoints to this piece.

Disclosures

The “Fundamental Thinking” series presents the perspectives of Harding Loevner’s analysts on a range of investment topics, highlighting our fundamental research and providing insight into how we approach quality growth investing. For more detailed information regarding particular investment strategies, please visit our website, www.hardingloevner.com. Any statements made by employees of Harding Loevner are solely their own and do not necessarily express or relate to the views or opinions of Harding Loevner.

Any discussion of specific securities is not a recommendation to purchase or sell a particular security. Non-performance based criteria have been used to select the securities identified. It should not be assumed that investment in the securities identified has been or will be profitable. To request a complete list of holdings for the past year, please contact Harding Loevner.

There is no guarantee that any investment strategy will meet its objective. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

© 2024 Harding Loevner

Disclosures

The “Fundamental Thinking” series presents the perspectives of Harding Loevner’s analysts on a range of investment topics, highlighting our fundamental research and providing insight into how we approach quality growth investing. For more detailed information regarding particular investment strategies, please visit our website, www.hardingloevner.com. Any statements made by employees of Harding Loevner are solely their own and do not necessarily express or relate to the views or opinions of Harding Loevner.

Any discussion of specific securities is not a recommendation to purchase or sell a particular security. Non-performance based criteria have been used to select the securities identified. It should not be assumed that investment in the securities identified has been or will be profitable. To request a complete list of holdings for the past year, please contact Harding Loevner.

There is no guarantee that any investment strategy will meet its objective. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

© 2024 Harding Loevner