Imagine your life without a television, a cell phone, or a computer. Or cameras. Imagine there aren’t and won’t be any electric vehicles. Or airplanes. Or fiber optics. Such a Thoreau-esque existence may appeal to some, but most people don’t want to live in an unwired cabin in the woods.

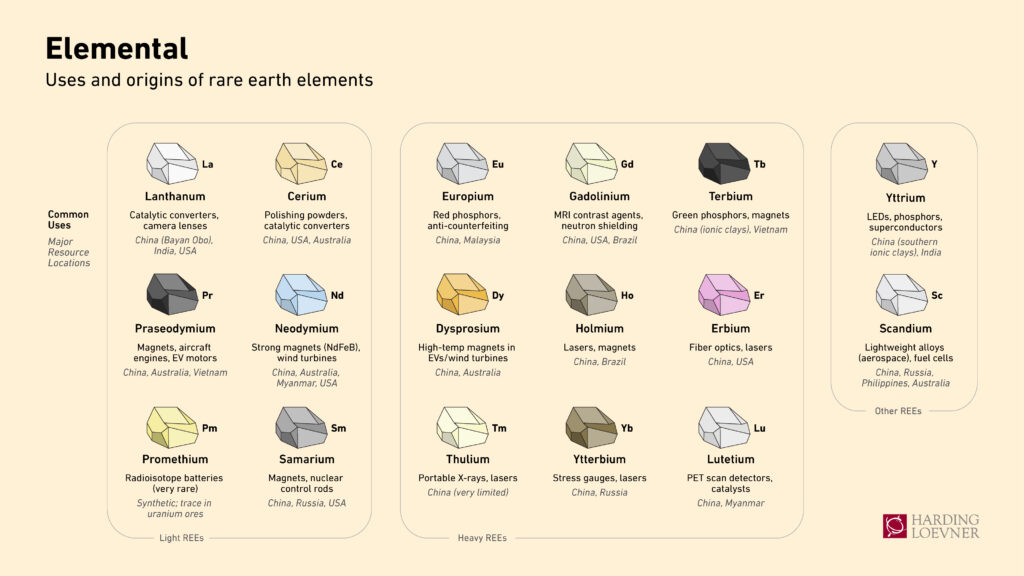

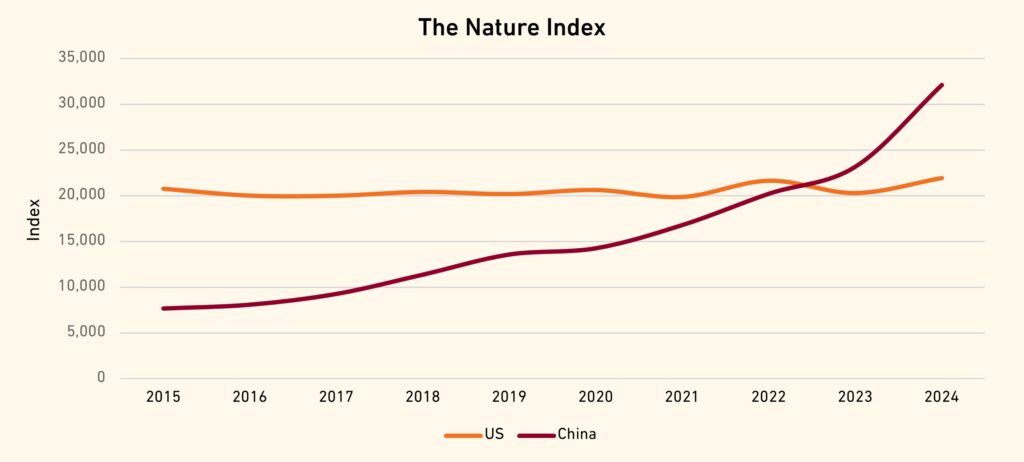

The US government has imagined it, all of it, because China holds the key to all those devices and more. A whole host of modern products require very tiny but critical amounts of what are called rare earth elements. They won’t work without these components. Over the past three decades, China has come to dominate the industry that mines and processes these elements. The US wants to change that.

It’s not just industrial competition. Rare earths are a critical chokepoint in accessing the modern world. China recently blocked the export of rare earths to western defense manufacturers, which could hurt the production of everything from bullets to fighter jets. The move was the latest tit-for-tat in the race for global supremacy between the world’s two largest economies. Because of that, the US has called these minerals critical to national security and made reviving a domestic rare-earths industry a priority. This has been a focus in both the current and former administrations.

Companies in the industry have gotten a boost from the attention. In July, the Department of Defense made a US$400 million equity investment in Las Vegas-based MP Materials. MP Materials, which owns the only fully operational rare-earths mine in the country—Mountain Pass in California—has signed contracts with the Department of Defense, General Motors, and Apple to supply magnets that incorporate rare earths. MP Materials’ stock, along with those of other rare earths miners operating in the US such as Lynas Rare Earths and Ramaco Resources, have risen sharply in recent months.

These efforts are an attempt to rebuild an industry that once existed in the US. Thirty years ago, about a third of all mined rare earths came from the US. Amid the globalization of the 1990s and 2000s, as China built up its capacity, the US and other countries ceded the territory. By 2011, China was mining 97% of all rare earths.

China is the leading supplier of ore, and it is also the biggest refiner of that ore. Mining is an industry where scale is paramount, the barriers to entry are high, the capital investments required are large, and the rivalry can be devastating. China’s domination of the industry will not be easy to offset, much less overtake.

Rare Earths Aren’t All That Rare

Despite the name, rare earth elements are not particularly rare. The name stems from when the elements were identified. They were discovered in “rare” oxide-containing minerals from a mine in Ytterby, Sweden. “Earth” comes from a term that was previously used to describe oxides in chemistry. Put them together, you get rare earth elements. But these minerals are found in lots of places, including China, the US, Australia, India, Russia, Brazil, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Significant deposits have been found in California, Wyoming, Alaska, Colorado, Missouri, Idaho, New Mexico, and New York.

There are 17 rare earth elements. Some of them are actually rare; promethium (used in radioisotope batteries), for example, shows up only in uranium ore. But others are fairly common. Cerium (used in catalytic converters) is the 25th most abundant element in Earth’s crust; it is more abundant than copper. There is a classification between heavy and light rare earths; the heavier ones are rarer than the lighter ones. Importantly for China, it has some of the most plentiful deposits of the heavy rare earths, giving it another advantage.

Breaking Up (Ore) Is Hard to Do

Finding the deposits is the first problem. The second, more significant problem, is mining them profitably. Scale is critical in mining—it takes years to invest in and build up the needed capacity, expertise, and people. Add in a national-security imperative and a focus by the world’s two leading superpowers and the field is likely to be even more challenging and combative.

The best way to analyze these dynamics is to employ the Porter Five Forces framework developed by Harvard business professor Michael Porter. This lets us examine the competitive dynamics of an industry and reveals its challenges.

Threat of New Entrants. The barriers to entry in rare earths-mining are high, which is a reason why China has been able to build its dominant position, making it difficult for others to compete. A key barrier to entry in mining is simply the access to ore. Finding it, and finding the kinds of high-grade ore that are less costly to process, is one challenge. Another is that unlike other elements, rare earth elements exist fused to other minerals and must be extracted through a complicated, and expensive, process. These factors make it difficult for new companies to succeed in the industry. This doesn’t mean US companies can’t compete—MP Materials does control the ore body at the Mountain Pass mine and Ramaco has a mine in Wyoming—but it will take a sustained effort and significant capital investments.

Bargaining Power of Buyers. Given China’s dominance of the industry, the bargaining power of buyers, who are wholly reliant upon the product, has been weak. The US government push to revive the industry (the Australian government is also taking strides to boost its domestic industry), however, is likely to strengthen buyer power. As federal agencies and large companies such as Apple and GM negotiate long-term contracts to help keep local, non-China based suppliers of rare earths afloat, these buyers will look to minimize prices. This is a mixed bag for companies in the industry. The effort to boost the industry may succeed, but it also may give buyers more options and stronger bargaining power longer-term. This is an underappreciated risk that could hurt profitability.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers. Processing rare earth elements requires specialized equipment and workers with expertise. This gives the industry’s equipment suppliers bargaining power over mining companies. Labor is also a challenge. Given the long drought in this industry in the US, there is a limited pool of workers with the specific knowledge and skills required for this kind of work. That gives them bargaining power over the companies as well.

Threat of Substitution. This is perhaps the area where the industry is the strongest, for the simple reason that currently there aren’t any alternative materials that easily replace rare earths.

Rivalry. Rivalry has been nonexistent, but may increase given the US government’s determination to rebuild the domestic industry. MP Materials is perhaps the most prominent US company right now, but it is not alone. Ramaco Resources recently released a preliminary economic assessment of its Brook Mine project in Wyoming, suggesting the project has a long-term EBITDA potential of US$143 a share per year, and a project life of more than 40 years. Lynas, an Australian company that trades in Canada, is building a processing plant in Texas. The combination of demand and government support is likely to lead to a situation where just as these companies are trying to build up their businesses, other companies are also sprouting up as well, which could lead to oversupply before any of them reach economies of scale.

The very thing that has some investors excited, therefore, is also a risk: the heavy role of government in the viability of these companies. What is good for the US government may not necessarily be good for minority shareholders. If these companies cannot show durable profit and growth without government support, is this truly a viable industry worth investing in?

There is a tough road ahead for sustainable growth and profitability in this industry, certainly for companies in the US, and even for companies abroad. The leading company in the industry, China Northern Rare Earth, supplied almost three quarters of all China’s rare earths, but its cash flow return on investment last year was only about 5%. In fact, over the past 20 years, its cash flow return on investment has been under 10% most years.

The rarest thing about rare earth elements ultimately may not be the elements themselves but profits and attractive returns for the companies trying to mine them.