For a century, revenues from a huge range of ubiquitous consumer products, from soap to diapers and from pet food to ice cream, have to a large extent been captured by a handful of giant consumer staples conglomerates such as Nestlé, Unilever, Colgate Palmolive, Kraft Heinz, and Procter & Gamble. Due to their unrelenting global expansion in recent decades, a high proportion of the world’s 7.5 billion people now use products from this handful of companies on a near-daily basis. The overall trend in the branded consumer staples industry has been one of continual consolidation, making these multinational corporations some of the highest returning businesses in the world, as well as some of the largest in terms of revenues and market capitalization. To illustrate their scale and growth, 22 Procter & Gamble brands now have revenues of over US$1 billion each, up from 10 in 2000, and Nestlé and Unilever combined employ over half a million people.

Source: Credit Suisse HOLT.

Locked Out Of The Profit Party

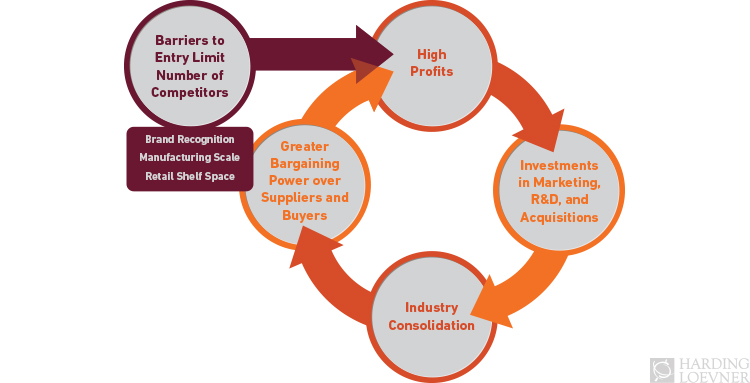

The steady growth of these consumer staples giants—many of them over a hundred years old—has largely been due to three key obstacles that have made it difficult for newcomers to enter the industry: the challenge of creating and sustaining brand recognition through continual product innovation and advertising, the high investment in manufacturing scale needed to compete beyond the local or regional level, and the ability to secure shelf space in major retail chains. By limiting the number of competitors, these obstacles, or “barriers to entry,” have allowed consumer staples conglomerates to avoid price competition from new entrants while achieving high profits through premium pricing afforded by brand differentiation. Put simply, the oligopolistic structure provides incentive for all major players to maintain high prices for mutual benefit.

“Few companies have been as well-placed to continuously extract profits from consumers and other industry players.”

These profits have been effectively reinvested in three ways to bolster their competitive advantage. First, investments in marketing have enabled these firms to keep their brands at the top of consumer’s minds, stimulating demand and prompting major retailers to stock their products. Second, consistently high R&D expenditure has allowed them to iterate existing products continually to keep pace with ever-changing consumer trends, thereby filling gaps between evolving consumer desires and current product offerings before newcomers can. Third, frequent acquisitions of smaller brands that manage to break through have kept the industry structure from fragmenting, keeping the profits with the major players. Consolidation has also endowed consumer staples conglomerates with significant bargaining power, allowing them to negotiate low prices from their suppliers, such as ingredients makers and packaging manufacturers, and demand high prices and prominent shelf space from retail chains such as Walmart and CVS Health.

Investments in R&D and brand acquisitions have also enabled these firms to expand horizontally into new product categories over time. For example, Kraft Heinz, which started as a cheese wholesaler in the early twentieth century, is now a major player in condiments through its Heinz and Grey Poupon brands, and Nestlé, which started in the Swiss infant food market in the 1860s, is now a major player in the global coffee (Nescafé), bottled water (Perrier, Poland Spring), and pet food (Purina, Friskies) industries. This horizontal expansion has brought about further consolidation, leading to even stronger bargaining power over their suppliers and buyers. This, in turn, continues to generate robust returns, which are then reinvested in marketing, R&D, and acquisitions, creating a virtuous cycle. According to Harding Loevner Analyst Sergei Pliutsinski, “Due to their favorable industry structure, the branded consumer staples conglomerates have formed a hegemony that has proven resilient for generations. In the world of commerce, few companies have been as well-placed to continuously extract profits from consumers and other industry players.”

The Virtuous Cycle of Consumer Staples Businesses

Closed Doors Crack Open

However, a confluence of new developments has begun to alter this competitive landscape, primarily by reducing the aforementioned barriers to entry. The first barrier, brand loyalty, is under fire from two fronts: wider product selection made possible by the unlimited shelves of e-commerce platforms, and proliferation of affordable online advertising opportunities, particularly on social media platforms, that can directly reach a target demographic. According to Pliutsinski, “Millennials in particular are seeking new brands that connect to them personally, and that they can engage with on their smartphones.” Furthermore, as Harding Loevner Analyst Maria Lernerman, CFA writes in Harding Loevner’s First Quarter 2017 Report for the Global Equity strategy, “Peer reviews, consumer-protection policies, and better shipping and return terms increasingly offered by the [e-commerce] platform sellers have lowered the risks of purchasing lesser-known brands,” giving e-commerce users greater confidence to trial products from little known new entrants.

The second barrier, manufacturing scale, is being undermined through the growth of contract and original design manufacturers that offer turn-key manufacturing services for new businesses, including the ability to prototype products affordably and scale up production volumes with nimble flexibility. The third barrier, access to shelf space in retail chains, is being weakened by the emergence of fulfillment and delivery services offered by e-commerce platforms, allowing new entrants to move products efficiently from factory to households. Additionally, growing consumer acceptance of online, mail, and otherwise direct-to-consumer merchandizing allows new entrants to bypass traditional retail gatekeepers.

“Even if just 1 in 10,000 of these new ideas catch on, it could erode the competitive seclusion long-enjoyed by branded staples conglomerates.”

In some cases, the tools to circumvent these barriers are packaged together, presenting new brands with an opportunity to catch on and scale up to the national or even global level with relative ease. A prime example is Amazon Launchpad, which partners with startup incubators and crowdfunding platforms to offer promising young businesses access to a product setup team, self-service marketing tools, Amazon.com’s customer service, Prime two-day shipping, pathways to sell in global markets, and exclusive discounts with companies that assist startups with prototyping, manufacturing, and branding.

Shaving Off Market Share

“In the past, new consumer staples products had almost exclusively been developed by a relatively small number of engineers in the R&D labs of a handful of branded goods conglomerates,” says Pliutsinski. “Now, people with dreams and just a small amount of startup capital can more readily enter the market, opening up a huge tail of potentially successful brands.” These changes have started to unleash entrepreneurs in categories long-dominated by established brands. In recent years, the number of attempts to enter the market has risen significantly, and smaller brands have grown faster both in relative and absolute terms, as evidenced by their recent gain in market share in the packaged foods industry. Pliutsinski remarks that “even if just 1 in 10,000 of these new ideas catch on, it could erode the competitive seclusion long-enjoyed by branded staples conglomerates.”

Source: Euromonitor

One idea that did catch on is the Dollar Shave Club, an exemplar of how new tools have allowed newcomers to capture market share from category incumbents. Launched in 2011 by two men who met at a party, Dollar Shave Club utilized online advertising, direct-to-consumer distribution, third-party order fulfillment and competitive pricing to capture a significant share of the men’s razor blade market. At the root of their success was an irreverent US$4,500 YouTube video that was widely shared on social media and has since been heralded as one of the best examples of online video marketing.

Dollar Shave Club’s first video

Credit: Dollar Shave Club

Before the entry of Dollar Shave Club, the US men’s razor blade industry had for decades essentially been a duopoly, dominated by Procter & Gamble’s 115 year old Gillette brand, trailed by Schick. With only two major competitors in the industry, price competition was almost non-existent, allowing Gillette to sell razor blades that cost 15 cents to make for as much as US$4.00 apiece. This competitive environment had more or less remained impervious to new entrants until Dollar Shave Club was able to break through in 2011 with their direct approach. According to Euromonitor, Dollar Shave Club, together with Harry’s—a similar startup—had captured 12.2% of the US men’s razor blade market by 2016, up from 7.2% in 2015. In an effort to regain market share, Gillette announced price cuts by as much as 20% in February 2017.

Shopping For Winners

But will we see equivalent Dollar Shave Clubs emerge in other consumer staples categories, or do these lowered barriers to entry merely offer challengers a temporary window of opportunity? And who stands to gain the most in either situation?

“The branded consumer staples giants have been around for generations and have withstood many competitive shifts before, including the destabilizing rise of Walmart and Costco.”

Though new entrants are perhaps in a stronger position now than they have been for decades, consumer staples companies still retain significant competitive advantages, including unrivaled manufacturing scale, synergies between divisions, and ownership of some of the strongest brands in history (Lipton tea and Colgate toothpaste come to mind). Perhaps more important is their financial strength—something newcomers lack—which allows them to invest heavily in innovation over the long haul. Hence, although some new entrants may come up with good ideas that gain traction initially, many will fail to keep up with shifting consumer tastes due to their much lower capacity to innovate over time, reducing them to one-hit-wonders that fade out as quickly as they storm in.

Credit: Lyza

Additionally, financial strength allows consumer staples conglomerates to be patient and either coopt the best ideas spurred by new entrants—Gillette recently launched its own direct-mail “shave club”—or pay premium prices to acquire successful upstarts when deemed advantageous to do so—Dollar Shave Club was acquired at a large premium by Unilever in late 2016 for US$1 billion, bringing it into the consumer staples conglomerate fold. A final strategy at their disposal is simply slashing prices to fend off new entrants who lack scale and capital, though history has shown that this strategy can lead to major long-term brand damage if not managed carefully.

There are already signs that some investors are viewing recently expanded opportunities for new brands as temporary: though venture capital deals for food and beverage companies rose sharply from 2009 (12 deals worth under US$250 million) to 2015 (123 deals worth over US$5 billion), these figures began to dip in 2016. “Don’t rush to the conclusion that these developments will have a deep impact,” says Pliutsinski. “After all, the branded consumer staples giants have been around for generations and have withstood many competitive shifts before, including the destabilizing rise of Walmart and Costco.”

Source: CB Insights, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

If new entrants do, in fact, prove successful and fragment the market, perhaps the most significant shift in the competitive landscape would be the rise in the bargaining power of suppliers, distributors, and, to a lesser extent, buyers. In this scenario, suppliers such as flavors and fragrances businesses could raise their share of industry-wide profits as they would be less reliant on contracts from, and therefore less compelled to accept low prices dictated by, the branded staples giants.

Amongst the buyers of branded consumer staples products, brick-and-mortar retailers could similarly stand to benefit from increased bargaining power. However, online retailers and distributors such as Amazon in the US, MercadoLibre in Latin America, and JD.com in China may find themselves in a better position than their brick-and-mortar counterparts as they stand to benefit from both market fragmentation as well as the shift toward e-commerce.

Though the precise impact these new tools will have on the competitive landscape is unclear, the battle lines have been drawn. “We’re still searching for more definitive answers as the branded consumer staples industry is changing,” says Pliutsinski. In this evolving environment, the stakes are high, the options are plentiful, and the winners and losers difficult to predict.

What did you think of this piece?

Contributors

Harding Loevner Analysts Sergei Pliutsinski and Maria Lernerman, CFA contributed research and viewpoints to this article.

Endnotes

“Lyza” image license available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Disclosures

The “Fundamental Thinking” series presents the perspectives of Harding Loevner’s analysts on a range of investment topics, highlighting our fundamental research and providing insight into how we approach quality growth investing. For more detailed information regarding particular investment strategies, please visit our website, www.hardingloevner.com. Any statements made by employees of Harding Loevner are solely their own and do not necessarily express or relate to the views or opinions of Harding Loevner.

Any discussion of specific securities is not a recommendation to purchase or sell a particular security. Non-performance based criteria have been used to select the securities identified. It should not be assumed that investment in the securities identified has been or will be profitable. To request a complete list of holdings for the past year, please contact Harding Loevner.

There is no guarantee that any investment strategy will meet its objective. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

© 2024 Harding Loevner

Disclosures

The “Fundamental Thinking” series presents the perspectives of Harding Loevner’s analysts on a range of investment topics, highlighting our fundamental research and providing insight into how we approach quality growth investing. For more detailed information regarding particular investment strategies, please visit our website, www.hardingloevner.com. Any statements made by employees of Harding Loevner are solely their own and do not necessarily express or relate to the views or opinions of Harding Loevner.

Any discussion of specific securities is not a recommendation to purchase or sell a particular security. Non-performance based criteria have been used to select the securities identified. It should not be assumed that investment in the securities identified has been or will be profitable. To request a complete list of holdings for the past year, please contact Harding Loevner.

There is no guarantee that any investment strategy will meet its objective. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

© 2024 Harding Loevner