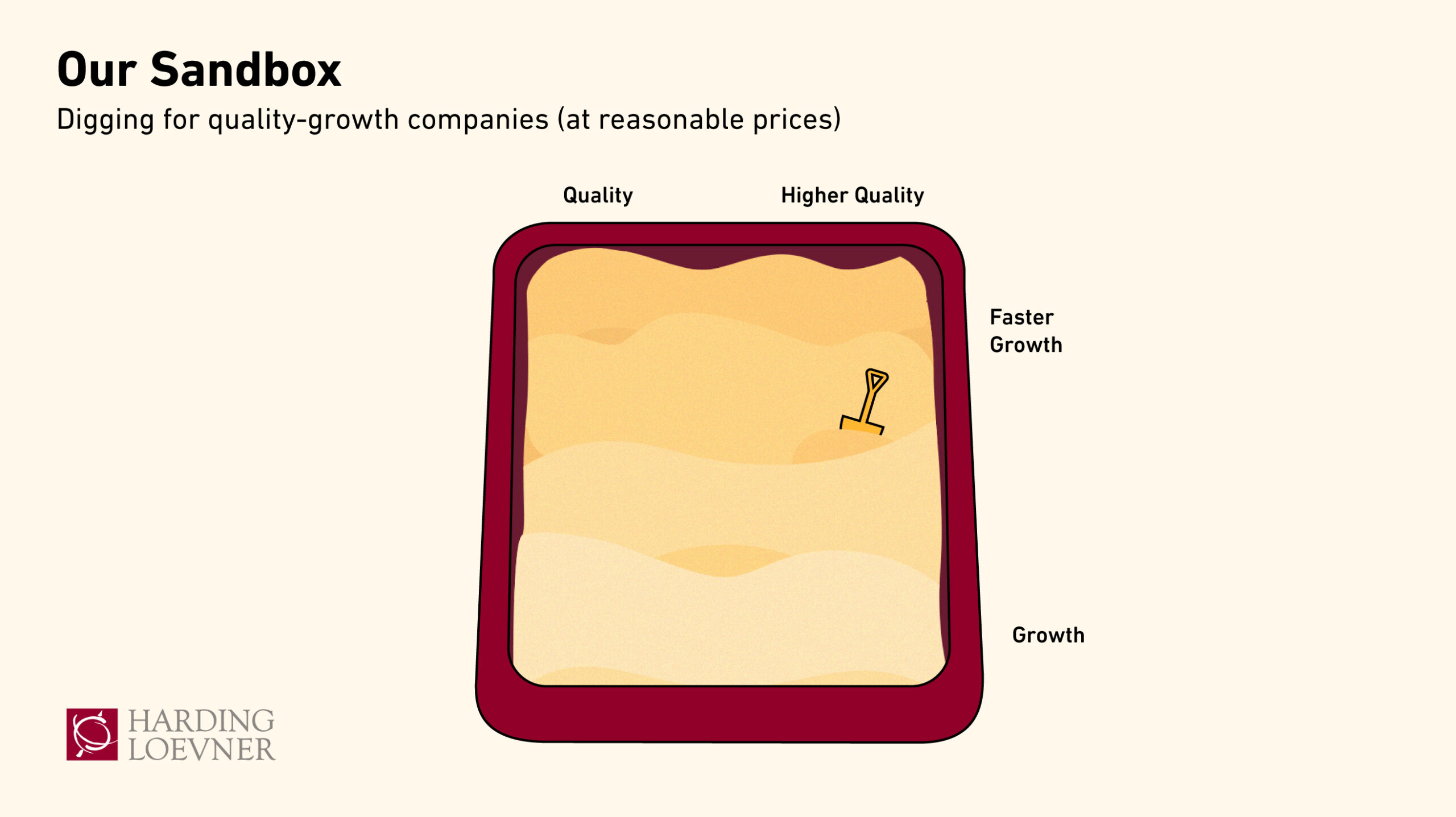

As quality-growth investors, we play in a certain sandbox. Think of the sand in ours as representing all the companies that we have determined meet our quality-growth criteria. Value investors have their own sandboxes, as do purely growth investors, momentum investors, and so on. But sandboxes are not static environments. They’re meant for digging.

Before we unpack this metaphor for our investment approach, it helps to first understand that all these neatly defined style boxes are a relatively recent phenomenon. Most investors today have only ever experienced a highly compartmentalized market that is data-saturated, quantitatively framed, and explained through a set of measurable “factors,” such as quality, growth, value, size, momentum—underlying characteristics of securities that are believed to influence returns. That wasn’t the case when Harding Loevner was founded almost 40 years ago. There was no detailed parsing of style factors, no granular quantitative definitions. Rather, equity investing was broadly divided into two styles, growth and value, and the closest thing to a “quality” factor was the vague notion of “blue chip” stocks.

Even the growth category used to be more of an idea than a well-defined factor. Whether a stock qualified as “growth” seemed to depend on the relative richness of its price-to-earnings or price-to-book multiple. The underlying logic was (and to some extent still is): if these are the stocks that trade at high multiples, you may as well trust the wisdom of the crowd.

So when our founders chose to focus on quality and growth, it wasn’t as if they landed on those factors after conducting a Fama-French-type analysis and deciding quality and growth were uniquely capable of delivering alpha. They wanted to own good quality companies, and they wanted those companies to grow—not in a speculative sense, but faster than the broad market and faster than industry rivals, as measured by actual business results, such as cash flows, earnings, and sales. They sought companies they could hold for a long time, guided by the belief that if you truly understood a business and its industry, and were willing to put up with the vagaries of the market over time, you could achieve superior long-term returns. Once they identified such businesses through deep company research, they bought the small minority whose shares were reasonably priced.

Because quality was not yet a defined factor, and our founders’ definition of growth (sustainable, profitable business growth) differed from the market’s (high stock-price multiples), it wasn’t a very concise pitch. That’s how our firm settled on the sandbox metaphor—and it still holds up, as greater rigidity in industry definitions hasn’t led to them being any better at describing how we invest. Over the decades, the industry has tried to fit every manager into a style box for the sake of comparison. You have probably seen a graphical representation like this before:

But, even today, we don’t think of our investments as falling somewhere along a value-to-growth continuum—a flawed framework, in our view, because it relies on both fundamental metrics and valuation metrics, blurring the distinction between company attributes and stock prices. Collapsing these two dimensions of investment analysis onto a single axis makes it easy to conflate signals about the “growthiness” of a portfolio’s holdings with their stock-price multiples. Instead, we think of our sandbox like this:

What’s different about our sandbox is that it doesn’t try to blend company analysis with stock valuation analysis. To be in our sandbox, a company’s underlying business has to meet four key criteria: it must have strong competitive advantages in its industry, quality management, high cash generation with all-weather borrowing capacity (markers of financial strength), and an industry structure that supports long-term profitable growth. The companies meeting our criteria that our analysts formally cover represent the full extent of our sandbox, and portfolio managers can purchase anything in it.

Where a company appears in that sandbox depends on how profitable or fast-growing it is. As with any sandbox, though, the sand shifts around. An industry’s competitive dynamics can change. Growth prospects can worsen or improve. The most desirable companies are often in the upper right corner, but because of our discipline in evaluating their fair value and not being willing to overpay to any significant degree, we’ll gravitate to other parts of the sandbox if there are more attractively priced opportunities there. After all, we’re sifting through the sand in search of quality and growth at a reasonable price.

What moves a lot more than the sand in our sandbox is the excitement or fear people have over a company’s growth prospects. When investors fixate on very rapid, short-term growth, they may overlook companies offering high long-term profitable growth, making their shares relatively less expensive. Those companies’ lower valuation multiples don’t automatically make them “value stocks,” and our buying them doesn’t turn us into value investors, which is the impression a standard style box might give. It just means that we’re finding growth at a more reasonable price.

So, while investors may focus on the industry’s standard style boxes and question when a manager begins to drift, the walls of our sandbox never change. We don’t chase a certain position in industry boxes, and any observable drift within our own sandbox is only ever the result of our day-to-day work of studying the attributes of individual companies and deciding whether their stock prices adequately compensate us for the risks. Industry definitions and analysis may continue to evolve, but our sandbox is firmly in place. ∎