In the US, one of the few developed countries where most medical insurance does not at least partially cover the cost, it runs people an average of $2,300 per ear to purchase and have fitted a pair of prescription hearing aids.1 That this strikes many as unreasonable—nor the fact that 98% of the world’s hearing aids are supplied by just five manufacturers—has not been lost on politicians.

So, three years ago, Congress decided it should do something about it. The “Over the Counter (OTC) Hearing Aid Act” calls on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to permit the sale of OTC hearing aids as an alternative to the high-fidelity instruments produced by Swiss-based Sonova, Danish manufacturers Demant and GN Nord, the privately held US-based Starkey, and WS Audiology, another private company based in Denmark and Singapore. Until now, any hearing device not sold through an accredited audiologist had to be labeled as a “personal sound amplification product (PSAP)” rather than a “hearing aid.” Such devices were held to loose performance and production standards. The idea behind the act was that establishing a new, more uniform category of devices able to be marketed as hearing aids, sold over the counter and self-fitted by consumers might encourage major consumer electronics makers to leverage their know-how in miniaturization and user-friendly app-based technologies to bring quality hearing aids to a wider swath of the American public. On The Stephen Colbert Show in October 2019, the bill’s co-sponsor, then-presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren, said the unaffordability of hearing aids was the one issue she and President Trump agreed on.

Later this fall, the FDA is expected to finish drafting the regulations in the act, having missed an earlier August deadline because of COVID-19-related priorities. Meanwhile, the pandemic has added to the winds of change blowing through the hearing aid industry. Millions of Americans in the prime demographic for hearing aids, older adults who are also among those most vulnerable to the virus, have been forced to weigh their hearing loss against infection risk from the close contact required for hearing aid fittings and tune-ups. At a time when everything from orthodontics to spin class has moved to an online direct-to-consumer sales model, are hearing aids the next product to get the Invisalign or Peloton treatment?

“I don’t know. People have been predicting disruption of the hearing aid industry for years,” says Patrick Todd, CFA, a Health Care analyst at Harding Loevner. “While it would be great to lower the cost of hearing aids in this country, I think many people underestimate the technological and anatomical barriers to creating a great hearing aid. The biggest proof of that is that almost every OTC hearing device ever sold in other countries has had minimal impact on the industry.”

“Every once in a while, I’ll wake up in the middle of the night wondering, ‘Is this the day Apple announces the world’s first truly breakthrough OTC hearing aid?’” says Patrick Todd, CFA, a Health Care analyst

at Harding Loevner.

Nevertheless, Todd acknowledges that the recent law and new competition it invites cause him to revisit his thesis. “Every once in a while, I’ll wake up in the middle of night wondering, ‘Is this the day Apple announces the world’s first truly breakthrough OTC hearing aid?’”

Can You Hear Me Now?

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 15% of the world’s adults2 live with some degree of hearing loss. Aging populations have supported steady growth for the hearing aid industry, with unit sales rising 4-5% annually over the past five years. Yet, even in developed countries, only 27% of people who could benefit from hearing aids have them. This is partly a function of the cost to the patient, and partly of the stigma still associated with using a hearing aid as a sign of aging. This, too, is something the entry of consumer brands could presumably help address. Increasingly, the generation of people entering their 40s and 50s and beginning to develop the first signs of hearing impairment will include many people who are comfortable not only with ordering products online, but also with in-ear audio technology, having spent much of their lives rocking ear buds. Already, premium hearing aids come with Bluetooth connectivity to a wide range of electronic devices. Perhaps it’s just a matter of time before hearing aids are viewed as less a sign of old age and more, like a Fitbit or Apple Watch, another category of branded bionics.

Up in Ears: Long-term Demographic Trends Support Future Hearing Aid Growth

Source: Sonova; US Census Bureau, International Programs, International Data Base, September 18, 2018.

First, though, any challengers will have to match the incumbents in enabling people to hear. Most age-related, so-called “sensorineural,” hearing deficiencies are the result of the inner ear’s own, less conspicuous, version of hair loss. As the body ages, repeated high decibel subway rides, rock concerts and, yes, too-loud ear buds damage the patches of tiny hair cells lining the inside of the cochlea that translate sound waves into electrical impulses processed by the brain as sound. High-quality hearing aids digitize sound, sort it into frequency bands, and amplify the bands where the cochlea is in need of a boost. Further, their sophisticated processors discern which sounds are worth amplifying and which are background noise that should be muted. Most existing PSAPs and over-the-counter models sold outside the US, by comparison, typically operate with limited frequency bands and only the most rudimentary filtering, leading to the common complaint that they sound “too loud.”

In the US today it is the audiologist’s responsibility to optimize these various functions according to the deficits of the individual ear. From the perspective of the manufacturers, this cuts two ways. Over time, many audiologists have become fiercely loyal to their favorite brand (and patients to their audiologist), creating a high barrier to new entrants. But it has also contributed to the costs of the delivered product, as manufacturers buy that loyalty with various financial incentives that support audiologists in bearing the high overhead of their low-volume, high-touch retail businesses. “People look at the concentrated industry structure and the price of hearing aids and assume the manufacturers are sitting on super-fat operating margins,” Todd says, “but that’s not really the case.” Indeed, while gross margins over the past several years have averaged 70%, a very large percentage of that, he says, goes to cover the costs of the audiologists.

In part to try to wrest more control over their distribution, manufacturers have increasingly moved down the path of forward integration. In Europe, where the major hearing aid companies have more brand recognition than in the US, Sonova and Demant have built their own fairly sizeable audiology networks. In the US, the manufacturers have sought to lock in their reach from behind the scenes, partnering with audiology chains, for example, through exclusive distribution agreements or low-cost financing programs to facilitate the purchase of franchises.

“The hearing aid companies love Costco,” Todd says. “Just because the retail price is low doesn’t mean they make way less on the sale. The wholesale margins are still quite attractive and off of a huge volume.”

Some large hearing aid retailers have also been integrating backward, licensing rights to their “house” brands. One of the more visible of these branding arrangements is Costco’s “Kirkland Signature” hearing aids (the same name used for all its private-label products, derived from the company’s original headquarters location, Kirkland, Washington), now licensed to Sonova. Although the big-box discounter had been selling hearing aids since the early 1990s, starting in the early 2000s it made a more serious commitment to the business, expanding the number of in-store audiology centers tenfold over the next 15 years. Today, between Kirkland Signature-branded Sonova devices and models from other manufacturers, Costco accounts for 12% of the US hearing aid market, the largest share of any retailer. Typically, it sells models a year or two behind the factories’ latest offerings but at half the price of the newer models that predominate on traditional outlets’ shelves. “The hearing aid companies love Costco,” Todd says. “Just because the retail price is low doesn’t mean the manufacturers make way less on the sale. The wholesale margins are still quite attractive and off of a huge amount of volume.”

Next Wave

Given its nondescript appearance, it can be easy to underestimate the amount of proprietary R&D that has gone into the creation of the modern hearing aid. Beyond continual refinements in sound quality, the profile of the devices has been shrunk to the point that some high-end models are completely, or almost completely, concealed in the ear canal.3 A major leap has also occurred just within the past few years with the introduction of rechargeable hearing aids. In addition to dispensing with the cost and annoyance of frequent battery replacement (recharging is typically done overnight in a tiny docking cradle), the move to a more compact lithium ion power source has enabled manufacturers to pack in more processing capability. This, in turn, has cleared the way for heavy media streaming and, thereby, further convergence of hearing aids with the whole wide world of consumer electronics.

Hearing aid-smartphone connectivity initially required users to carry a bridging device to translate Bluetooth into another protocol that could be understood by the hearing aid. In 2013, GN and Apple cracked the code enabling GN’s hearing aids to pair directly with the latest iPhone. More recently, other manufacturers and Google have developed their own protocols, allowing more users to seamlessly stream music, communicate with voice assistants, answer the phone and doorbell, and adjust the volume and settings on the hearing aids themselves, all via an app.

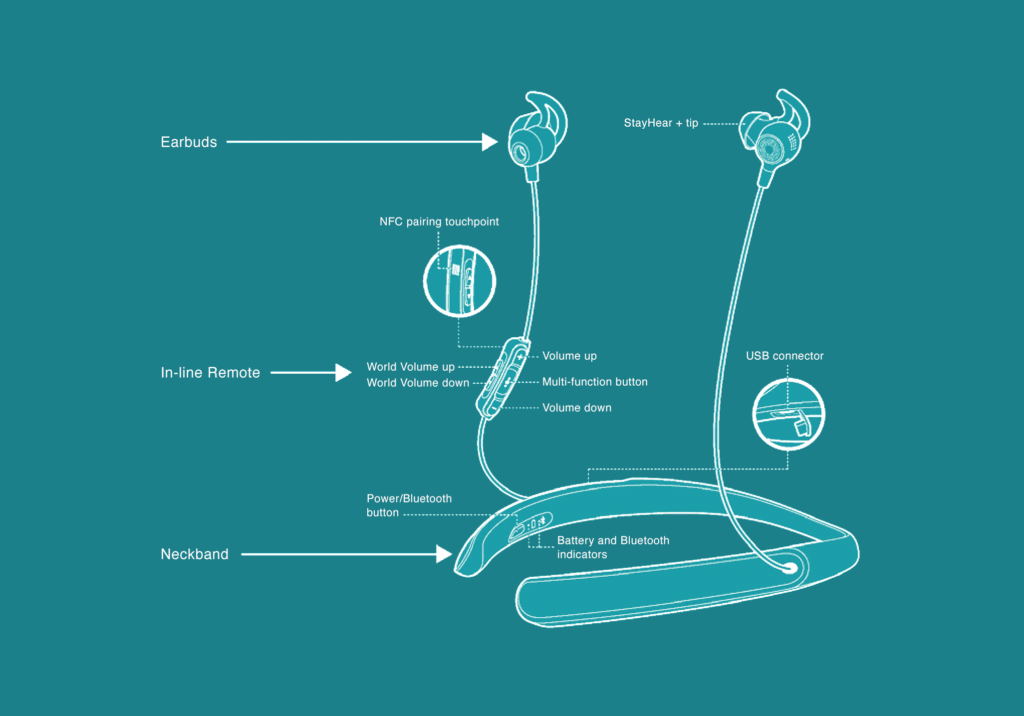

Bose was the first major consumer electronics manufacturer to take the next step toward making its own hearing aid device. In 2014, the company acquired a startup called Ear Machine, which at the time was working with National Institutes of Health to test app technology that allowed users to perform some of the programming traditionally in the purview of an audiologist. Bose incorporated the technology into its Hearphones, a $499 OTC PSAP. Customer reviews were generally positive, and the company then set about refining the technology and lobbying lawmakers for the right to market it as an actual hearing aid. In 2018, based on its prototype, Bose was granted preliminary approval reserved for novel applications pending FDA completion of the guidelines, effectively becoming the first OTC hearing aid under the new law.

Although the company has so far offered few details about the new product, some can be surmised from its filings with the FDA: Using an app, a user can adjust gain and compression parameters across 12 frequency bands, including options to correct tone, balance volume between the ears, and select three levels of focus on sounds directly in front of the person. Outwardly, sound is captured by a pair of ear buds connected by wires to a flexible lithium battery worn around the base of the neck. In form and function, in other words, the new Bose OTC hearing aid appears to operate almost exactly as its old hearing headphones.

Based on preliminary designs filed with the FDA, above, Bose’s new OTC “hearing aid” seems to look and operate almost identically to its existing Hearphones product.

Source: accessdata.fda.gov.

Apple has been even less forthcoming about its hearing aid plans. Although the company has been vocal about its commitment to its healthcare initiatives and the hearing community is frequently abuzz with rumors of potential developments, the most recent consumer healthcare announcement concerned a new, blood-oxygen-measuring app for the Apple Watch, not a hearing aid.

“I think the consumer manufacturers are finding the challenge of making a hearing aid more difficult than they thought,” Todd says. “Bose and Apple both make great products, but a big part of their appeal comes from the brand association. In my discussions with industry people, 90% of their time and effort is spent on convincing customers they need a hearing aid and lowering the profile of the device. I’m not sure you can assume that just because someone is proud to wear earbuds, they will feel the same way about a hearing aid. And if a device already has terrific sound quality and allows you to stream and make phone calls, and you can’t see it anyway, does it really matter if it’s an Apple?”

Meanwhile, the new OTC device makers are not the only ones moving online. During the pandemic, some audiologists have joined the telehealth trend and begun shipping portable digital hearing-measurement devices to patients at home. Hearing aid manufacturers have moved in a similar direction, expanding on and promoting their own “teleaudiology” tools for remote device troubleshooting, and pushing software updates and customer-specific adjustments directly to patients’ hearing aids through the cloud.

Todd says it will be interesting to see how the new OTC law interacts with these developments and further helps to shape the competitive landscape. “In addition to more competition, I think you’re going to see some unbundling of products and services that results in higher price transparency,” he says. It is possible, for example, that as manufacturers continue to evolve their remote offerings they use the opportunity to wean themselves from their interdependency with the audiology profession and introduce their own lower-priced tier of self-fitted models. Todd sees a recent Demant licensing agreement, under which Costco is selling its hearing aids under the Philips label, as a potential step in this direction. “By linking up with a recognized consumer electronics brand, I think they’re looking ahead to a time when some of their products could sit on retail shelves and websites by themselves.”

If self-fitting trends accelerate, there is a risk that incumbent manufacturers could find themselves stuck with obsolete distribution networks. But they, too, have the opportunity to move from selling to and serving patients mostly from brick-and-mortar to mostly online, navigating the shift as many companies in other industries have. In that case, the traditional industry’s overall sales and margins could ultimately grow through increased penetration rates and lower distribution costs for hearing aids. Higher hearing aid company profits might not be exactly the result that Elizabeth Warren and President Trump had in mind, but it would still mean more Americans having access to hearing aids—and that a great long-term investment opportunity plays on.

What did you think of this piece?

Contributors

Analyst Patrick Todd, CFA contributed research and viewpoints to this piece.

Endnotes

1This lack of insurance coverage includes Medicare. The one notable exception to the high out-of-pocket costs for hearing aids in the US is the Veteran’s Administration (VA), which provides premium devices to VA-qualified veterans, free of charge.

2Some 32 million children under the age of 15 also suffer hearing loss, most a result of congenital conditions. This is a more widely-served market than age-related hearing loss, the product of higher rates of insurance coverage and rapid adoption in the past decade of cochlear implants. The industry that serves it is also highly concentrated, with just three companies (including Sonova, also a member of the Big Five) controlling 98% of the implant market.

3Some people’s ear canals are simply too narrow for so-called invisible hearing aids to fit entirely inside. In such cases, a portion of the device may still be visible, or it may not be an appropriate option at all.

Disclosures

The “Fundamental Thinking” series presents the perspectives of Harding Loevner’s analysts on a range of investment topics, highlighting our fundamental research and providing insight into how we approach quality growth investing. For more detailed information regarding particular investment strategies, please visit our website, www.hardingloevner.com. Any statements made by employees of Harding Loevner are solely their own and do not necessarily express or relate to the views or opinions of Harding Loevner.

Any discussion of specific securities is not a recommendation to purchase or sell a particular security. Non-performance based criteria have been used to select the securities identified. It should not be assumed that investment in the securities identified has been or will be profitable. To request a complete list of holdings for the past year, please contact Harding Loevner.

There is no guarantee that any investment strategy will meet its objective. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

© 2024 Harding Loevner

Disclosures

The “Fundamental Thinking” series presents the perspectives of Harding Loevner’s analysts on a range of investment topics, highlighting our fundamental research and providing insight into how we approach quality growth investing. For more detailed information regarding particular investment strategies, please visit our website, www.hardingloevner.com. Any statements made by employees of Harding Loevner are solely their own and do not necessarily express or relate to the views or opinions of Harding Loevner.

Any discussion of specific securities is not a recommendation to purchase or sell a particular security. Non-performance based criteria have been used to select the securities identified. It should not be assumed that investment in the securities identified has been or will be profitable. To request a complete list of holdings for the past year, please contact Harding Loevner.

There is no guarantee that any investment strategy will meet its objective. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

© 2024 Harding Loevner